Introduction to Sera Monastery

Essay

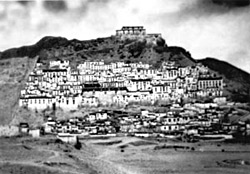

Located about two miles north of LhasaLha sa, and occupying an area of about one-third of a square kilometer, Sera Monastery (Sera Gön/se ra dgon) is one of the three great monasteries (drasa/grwa sa) or seats (densa/gdan sa) of the GelukDge lugs school of Tibetan Buddhism. According to tradition, TsongkhapaTsong kha pa (1357-1419), the founder of the GelukDge lugs school, composed his commentary on Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, entitled The Ocean of Reasoning (Rikpé Gyatso/Rigs pa’i rgya mtsho), in a small hermitage called Sera ChödingSe ra chos sdings in the foothills just above SeraSe ra around the year 1409. In the midst of writing this work, one of the folios of the text flew into the air in a gust of wind. It began to emit “A” letters (the symbol of the perfection of wisdom) in the color of molten gold. Some of the letters dissolved into a stone at the base of the hill and permanently imprinted themselves on it.

Witnessing this, TsongkhapaTsong kha pa prophesied that this would be the future site of a great center of Buddhist learning, an institution of particular importance for the study and practice of the Madhyamaka doctrine of emptiness. A decade later, Jamchen Chöjé Shakya YeshéByams chen chos rje shā kya ye shes (1354-1435), a close disciple of TsongkhapaTsong kha pa, founded SeraSe ra at this very site.

Originally a monastery for the study and practice of tantra, some of SeraSe ra’s early preceptors steered the monastery in a more scholastic/philosophical direction shortly after its founding. SeraSe ra quickly began to attract large numbers of monks, causing the third SeraSe ra throne holder, Gungru Gyeltsen ZangpoGung ru rgyal mtshan bzang po (1383-1450), to partition the monastery into four colleges (dratsang/grwa tshang): GyaRgya, Drom’Brom TengSteng, TöStod, and MéSmad. An early reorganization consolidated these into two colleges, the Upper (TöStod) College and the Lower (MéSmad) College. In the latter half of the fifteenth century the TöStod College was absorbed into a new college called JéByes. For over two centuries, then, these were the only two colleges at SeraSe ra. But then in the early eighteenth century the last of SeraSe ra’s colleges, the NgakpaSngags pa College, was founded. Since that time SeraSe ra has had three colleges: JéByes, MéSmad and NgakpaSngags pa.

The JéByes and MéSmad Colleges are philosophical colleges (tsennyi dratsang/mtshan nyid grwa tshang), with a twenty-year-long curriculum of studies culminating in the prestigious geshé/dge bshes degree. The NgakpaSngags pa College is an institution dedicated to the practice of tantric ritual (kurim dratsang/sku rim grwa tshang). Before 1959 each college had its own administration, headed by its own abbot. The so-called Council of Ten Lamas (LakhachuBla kha bcu) – under the leadership of the abbots of the three colleges – administered the affairs of the monastery as a whole.

The Lawa KhangtsenLwa ba khang tshan of the JéByes College, one of the larger regional houses at SeraSe ra.

Until 1959, monks from all over Tibet came to study at SeraSe ra’s two philosophical colleges. These two colleges – JéByes and MéSmad – eventually developed sub-units of their own, called “regional houses” (khangtsen/khang tshan). The regional houses – thirty-five in number – are organized chiefly along geographical lines, and monks from different regions of the country usually entered the house that corresponded to their specific region. Regional house buildings take up the largest part of the monastery. SeraSe ra also has four major temple complexes: one belonging to each of the three colleges, and then the SeraSe ra Great Assembly Hall (Tsokchen/tshogs chen), where the monks from all of the colleges would meet as a whole.

Before 1959, the monastery had a population of between eight thousand and ten thousand monks, although not all of these monks were in residence in the monastery at any one time. By some estimates, only 25 percent of these monks were “textualists” (pechawa/dpe cha ba), that is, monks engaged in study. The remaining monks were workers, many of whom belonged to “punk-monk” (dop dop/ldob ldob) fraternities (lingkha/gling kha).

A photo of a dop dop/ldob ldob, or “punk-monk,” taken sometime before 1959.

Like all of the three seats, the monastery subsisted financially through funding from a variety of sources that included (1) proceeds from its estates, (2) contributions from the Tibetan government, (3) contributions from lay patrons, and (4) business ventures of various sorts. Individual monks were supported by means of contributions from a variety of sources that included the monastery (SeraSe ra), the college, the regional house, lay patrons, their teachers, and their family. Many monks also engaged in private business ventures.

In Tibet, after the events of 1959, SeraSe ra’s monks were forced to leave the monastery, and it became an army barracks for a number of years. When official Chinese government policy toward religion changed in the early 1980s, monks were allowed to return to SeraSe ra. It is largely through their efforts that most of the buildings in the monastery have been rebuilt or restored. Many of the buildings that were destroyed have been rebuilt.

In time, these monks also reestablished much of the educational system and ritual life of the monastery. The two philosophical colleges, however, no longer function as separate institutions, and all textualist monks today follow the same set of textbooks (that of the JéByes College). They also debate together (something that was not the case prior to 1959). In 2002, SeraSe ra-Tibet had a monastic population of about five hundred “official monks” and about half that number of “unofficial monks” (monks awaiting formal admission into the monastery). Chinese official policy limits the number of official monks at SeraSe ra to 550. A “democratic board” (mangtso daknyer uyön lhenkhang/dmangs gtso bdag gnyer u yon lhan khang) – consisting of five directors of varying seniority, seven representatives and one secretary – governs the affairs of the monastery today.

Tsangpa KhangtsenTsang pa khang tshan, one of the compounds of SeraSe ra-Tibet that was totally destroyed. The rebuilding of this regional house was completed in the early 1990s.

In 1970, after a decade of living in temporary residences in various parts of India (principally in Buxador), refugee monks from SeraSe ra in India reestablished another SeraSe ra in the Bylakuppe settlement (Karnataka State).

These monks, only two hundred of them originally, also reestablished the educational and ritual life of the college along traditional lines, and today it grants the various kinds of geshé/dge bshes degrees in much the same way as the original monastery did before 1959. SeraSe ra-India has a governance structure similar to the original administrative structure of the monastery before 1959. The NgakpaSngags pa College was not initially re-established at Bylakuppe, but has recently been revived as a separate institution in a nearby settlement. Physically about the same size of the original Sera Monastery in Tibet, in 2002, the monastery in Bylakuppe had a monastic population of about four thousand. Today, both in India and in Tibet, the monks who enter the monastery are presumed to be textualists – serious, full-time students. This means that the institution of the professional worker-monk is now all but defunct. Thus, as with much of Tibetan society today, SeraSe ra exists as a culturally bifurcated phenomenon: one version of SeraSe ra in Tibet, and the other in the Indian diaspora.

A view of some of the larger temples of SeraSe ra-India from one corner of the monastery.

We should also note that SeraSe ra has had an impact far beyond the borders of either SeraSe ra-India or SeraSe ra-Tibet. In Tibet before 1959 the two philosophical colleges of SeraSe ra – JéByes and MéSmad – each had several branch monasteries (yenlakgyi gönpa/yan lag gi dgon pa) and temples under their control. These were sometimes located far from LhasaLha sa, but many were located in (or in the environs of) the capital. For example, the various hermitages located in the hills above SeraSe ra all belonged to SeraSe ra, or to its high lama/bla mas. There was also the famous monastery/temple of Drapchi Lhamo, located between SeraSe ra and LhasaLha sa, as well as the monastery of TsemönlingTshe smon gling, located in LhasaLha sa proper. SeraSe ra also had ties to other GelukDge lugs monasteries throughout Tibet. These were the institutions, sometimes quite large, that would send monks for advanced studies to SeraSe ra.

A photo of Ganden ChönkhorDga’ ldan chos ’khor Monastery in Shang Principality, TsangGtsang, Western Tibet, taken before 1959. This is one of the monasteries affiliated with SeraSe ra. It was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Courtesy of Ven. Lhundub and Ven. Thabkay.

Before 1959 monks who came from these monasteries were called “continuing monks” dragyün/grwa rgyun in so far as they were traveling from their gzhi dgons for continuing education. (In today’s parlance we might call these “transfer students.”) In this way SeraSe ra enjoyed a variety of institutional relationships that radiated throughout all of Tibet. At least this was the case before 1959. Today, this web of relationships barely exists: in part because many of the branch monasteries have been destroyed, and in part because the Chinese government’s method of partitioning ethno/cultural Tibet creates impediments for monks who must cross provincial boundaries to enter SeraSe ra.

Outside of Tibet, since the late seventies senior monks from SeraSe ra-India have founded a variety of monasteries and “dharma centers” throughout the world. What was before 1959 a relatively culturally isolated community has, therefore, through the process of diaspora, globalization, and missionary activity achieved a transnational presence that would have been thought inconceivable just half a century ago.

Glossary

Note: The glossary is organized into sections according to the main language of each entry. The first section contains Tibetan words organized in Tibetan alphabetical order. To jump to the entries that begin with a particular Tibetan root letter, click on that letter below. Columns of information for all entries are listed in this order: THL Extended Wylie transliteration of the term, THL Phonetic rendering of the term, the English translation, the Sanskrit equivalent, the Chinese equivalent, associated dates, and the type of term. To view the glossary sorted by any one of these rubrics, click on the corresponding label (such as “Phonetics”) at the top of its column.

| Ka | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sku rim grwa tshang | kurim dratsang | tantric ritual | Term | |||

| Kha | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| khang tshan | khangtsen | regional house | Term | |||

| Ga | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| gung ru rgyal mtshan bzang po | Gungru Gyeltsen Zangpo | 1383-1450 | Person | |||

| grwa rgyun | dragyün | continuing monk | Term | |||

| grwa tshang | dratsang | college | Term | |||

| grwa sa | drasa | great monastery | Term | |||

| gling kha | lingkha | fraternity | Term | |||

| dga’ ldan chos ’khor | Ganden Chönkhor | Monastery | ||||

| dge lugs | Geluk | Organization | ||||

| dge bshes | geshé | Term | ||||

| rgya | Gya | Organization | ||||

| Nga | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| sngags pa | Ngakpa | Tantric | Organization | |||

| Ta | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| steng | Teng | Organization | ||||

| stod | Tö | Organization | ||||

| Da | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| gdan sa | densa | seat | Term | |||

| ldob ldob | dopdop | punk-monk | Term | |||

| Pa | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| dpe cha ba | pechawa | textualist | Term | |||

| Ba | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| byams chen chos rje shā kya ye shes | Jamchen Chöjé Shakya Yeshé | 1354-1435 | Person | |||

| byes | Jé | Organization | ||||

| bla kha bcu | Lakhachu | Council of Ten Lamas | Organization | |||

| bla ma | lama | Term | ||||

| dbu ma rtsa shes | Uma Tsashé | Root Verses on the Middle Way | Mūlamadhyamakakārikā | Text | ||

| dbu ma lha khang | Uma Lhakhang | Madhyamaka Temple | Building | |||

| ’brom steng | Dromteng | Organization | ||||

| Ma | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| dmangs gtso bdag gnyer u yon lhan khang | mangtso daknyer uyön lhenkhang | democratic board | Term | |||

| smad | Mé | Organization | ||||

| Tsa | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| tsang pa khang tshan | Tsangpa Khangtsen | Building | ||||

| tsong kha pa | Tsongkhapa | 1357-1419 | Person | |||

| gtsang | Tsang | Place | ||||

| Tsha | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| tshe smon gling | Tsemönling | Monastery | ||||

| tshogs chen | Tsokchen | Great Assembly Hall | Building | |||

| mtshan nyid grwa tshang | tsennyi dratsang | philosophical college | Term | |||

| Zha | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| gzhi dgon | zhigön | home monastery | Term | |||

| gzhi bdag dge gnyen | zhigön | Layman Lord of the Place | Buddhist deity | |||

| Ya | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| yan lag gi dgon pa | yenlakgyi gönpa | branch monastery | Term | |||

| Ra | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| rigs pa’i rgya mtsho | Rikpé Gyatso | The Ocean of Reasoning | Text | |||

| La | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| lwa ba khang tshan | Lawa Khangtsen | Building | ||||

| Sa | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| se ra | Sera | Monastery | ||||

| se ra dgon | Sera Gön | Sera Monastery | Monastery | |||

| se ra chos lding | Sera Chöding | Monastery | ||||

| Ha | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| lha sa | Lhasa | Place | ||||

| Sanskrit | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| nāgārjuna | Person | |||||

| madhyamaka | Doxographical Category | |||||

| tantra | Term | |||||

| Chinese | ||||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Chinese | Date | Type |

| shang | Place | |||||