An Introduction to the Hermitages of Sera

As the saying goes, “Sera is surrounded by hermitages, Ganden is surrounded by self-arisen images, and Drepung is surrounded by dharma protectors.” Sera Mahāyāna Monastery (Sera Tekchen Ling) is therefore surrounded by hermitages as numerous as the stars on the fifteenth day of the lunar month.

Introduction

Among the three great seats of learning of the Geluk school, Sera is the one renowned for its hermitages (ritrö). At least nineteen such institutions are found tucked away in the mountains behind and around Sera.2 In this section of the Sera Project website, you will learn more about each of these hermitages. To go directly to the Hermitages interactive map, please click here.

The Tibetan compound word ritrö – the word that we translate here as “hermitage” – literally means “in the midst of” or “on the side of” (trö) “the mountains” (ri).3 Hermitages are small monasteries found in relatively isolated mountain locations. At least in their early stages, they were the homes of individuals variously called “retreatant” (tsampa), “meditator” (gomchen), “recluse” (chikbupa or ensapa), and of course “hermit” (ritröpa). A hermitage often began as the residence of a single individual,4 but most of them grew. When they became relatively large, they often ceased to be called hermitages and began to be called “monasteries” (gönpa), but the dividing line between these two terms – hermitage and monastery – is fuzzy. There are some hermitages, for example, that have more monks than many institutions that bear the name “monastery.” Many of Tibet’s greatest monasteries began as the hermitages of individual monks.

Hermitages usually begin as the retreat places of individual monks, tantric priests (ngakpa), pious male lay practitioners and, less frequently, nuns and laywomen.5 They are the places where these individuals settled for intensive, solitary practice. Originally, these sites may have had no buildings at all but only caves. When a cave did not exist, a monk might have built a simple stone and mud hut for his personal use. A monk often chose as the site of his hermitage a place that was considered holy (né tsa chenpo) – places where former saints had lived, places associated with certain deities, or places marked by certain geosacral signs such as self-arisen images or magical springs with curative powers. Holy places are said to bring blessings (jinlap) to those who reside there. Like a magnifying glass, they have the power to amplify or increase the merit derived from any religious practice performed there, and in general they are said to increase the chances of success in religious practice.

What would a monk have done in his hermitage? He would have engaged in meditation, ritual, study, writing, memorization, and a host of spiritual practices classified together under the general rubric of “ accumulation and purification” (sakjang).6 Or he might have engaged in a combination of all of these various activities. Even monks who were not committed to eremiticism as a permanent way of life often settled in isolated locations for limited periods of time – for example, when they engaged in short or longer-term deity-focused practices like the so-called “enabling retreat” (lerung) or “approximation retreat” (nyenpa).7

Many hermits traveled widely before settling on one spot as their permanent residence. And some, of course, never settled at all, but remained itinerant throughout their entire lives. Those monks who chose to settle usually picked a site that provided them with privacy. But the site also had to be relatively close to a populated area – close enough to allow them to obtain food and other necessities (usually in the form of donations from the laity). After remaining at a particular site for some time, the monk might gain a certain level of renown. In this case, he might attract students. If he did, an institution would begin to coalesce around him. First, students would build their own huts close to that of their master, and eventually they might build a temple where the monastic community could come together for rituals and teachings. If the community managed to attract the financial sponsorship of lay patrons, the hermitage would grow. When the original lama-founder died, the reincarnation might be identified, and in this way the succession would be maintained, and the hermitage would continue to develop as an institution. This is how private retreats evolved into more formal hermitages, and (in some instances at least) into larger monasteries. This is a well-known pattern in the history of Tibetan religious institutions. It is a model applicable not only to the evolution of Sera’s hermitages but also to other monasteries throughout Tibet.

Location and Institutional Affiliation to Sera/Se ra

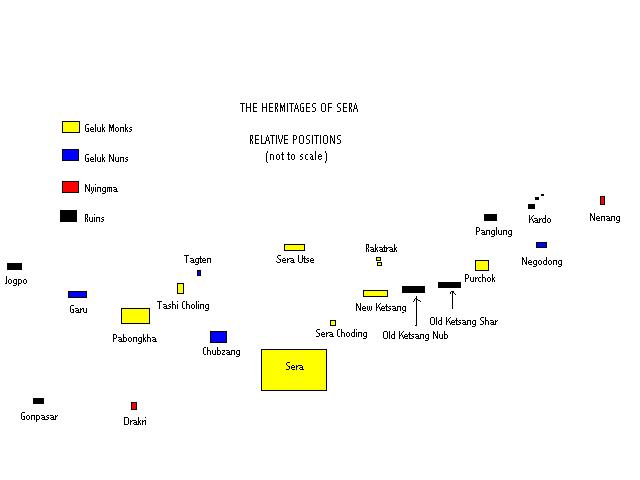

Most of the Sera hermitages are located in the mountains to the north, east and west of the monastery along a (roughly) fifteen kilometers east-west span from Jokpo and Gönpasar hermitages in the far west to Nenang in the far east. The rough map that follows gives the relative location and some basic information about the hermitages of Sera as of 2004. The map operates on a usual north-south axis, with the mountains to the north of the hermitages and the city of Lhasa to the south. The hermitages to the right (northeast) of Sera are located in what is today a suburb of Lhasa known as Dodé.8 The hermitages to the left (northwest) of Sera are located in the suburb known as Nyangdren.

In 1959, all of the hermitages on this map were thriving institutions. Two of them – Negodong to the east, and Garu to the west – were nunneries. The rest were monasteries for male monks. They ranged in size from about ten to well over one-hundred monks or nuns. In the case of monks’ hermitages, it was not uncommon for there to have been a core group of six to eighteen fully-ordained monks (gelong) that is what gave the institution its formal status and legitimacy as a monastery. But all of the monasteries also had many novices, non-monastic lay workers and support staff. If the hermitage was also the seat of a labrang or lama’s estate/household, the support staff (including novices) could be three to four times as large as the number of fully ordained monks. For example, the Keutsang West Hermitage (Keutsang Nup Ritrö), the official residence of the Keutsang Lamas, had a core group of twenty-five fully ordained monks, but if one includes novices and non-monastic staff the population was closer to ninety.9

Of the nineteen Sera hermitages nine were the seats of lamas – that is, they were the headquarters for lama’s estates. With two exceptions (noted below) the name of the lama lineage and that of the hermitage were identical. The lama’s estate hermitages were:

- Jokpo

- Gönpasar

- Drakri

- Trashi Chöling, since 1930 the seat of the Pabongkha Trülkus

- Sera Utsé, the seat of the Drupkhang Trülkus

- Keutsang West

- Purchok

- Panglung

- Khardo

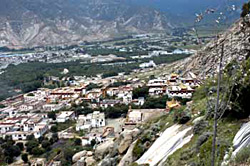

Sera as viewed from Chöding Hermitage (Chöding Ritrö).

Despite the fact that all of the hermitages are called “hermitage of Sera” (Seré ritrö), their relationship to Sera is actually quite varied and often shifts over time. Some are related to Sera only insofar as they were founded by Sera monks, or because as they were taken over by Sera monks at some point in their history. In several cases, hermitages were independent institutions with only nominal ties to Sera. In other instances, hermitages were actually the property of Sera. In between these two poles – minimal affiliation to Sera at one extreme, and ownership by Sera at the other – there were a variety of kinds and degrees of affiliation. If the hermitage belonged to a Sera lama, then it was this lama, and not Sera, who owned the hermitage. But even then there could be different degrees of affiliation between Sera and the hermitage.

For example, in 1959 Keutsang West belonged to the Keutsang Lama. All of the monks of the hermitage belonged to the Keutsang Lama’s estate (Keutsang Labrang). But all of the official monks of Keutsang were also official monks of the Hamdong Regional House (Hamdong Khangtsen) of Sera Jé College (Sera Jé Dratsang), and enjoyed all of the privileges of being Sera monks with regional house affiliations.10 Purchok Hermitage (Purchok Ritrö), by contrast, appears to have been much more independent, and had a weaker affiliation to Sera. Purchok monks belonged principally to the Purchok Lama’s estate (Purchok Labrang), and it appears that many (perhaps most) did not have official membership in either the Jé College or in one of its regional houses.

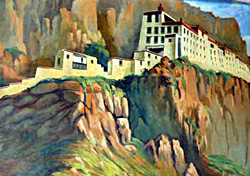

A painting of what Keutsang West Hermitage looked like before 1959.

To take another example, the nunneries11 of Garu and Negodong belonged not to Sera but to the lama’s estates of the Drakri and Khardo lamas, respectively, and these lamas served as their abbots. It is clear, then, even from these few examples, that the question of the institutional relationships of these hermitages to Sera is a complex one. Because few elder monks from these various monasteries are still alive, it is a challenge to piece together the kinds of affiliation that the various hermitages had to Sera before 1959. This is something that in many cases still remains to be determined.

Clearer is the present status of the hermitages today. In 2004, hermitages were either independent institutions or they belonged to – in the strong sense of being staffed and run by – Sera. Of the twelve hermitages that are still active (i.e., that are not in ruins) and that remain Geluk, five belong to Sera: Jokpo, Pabongkha, Sera Utsé, Sera Chöding, and Rakhadrak. The other three male-monk hermitages (Trashi Chöling, Keutsang and Purchok) and the four nunneries (Garu, Takten, Chupzang, and Negodong) are independent institutions. The affiliation of a hermitage today is largely the result of who claimed and rebuilt it after the Lhasa municipal government began to give permits for this purpose in the 1980s. Sera laid claim to the five hermitages it owns today. It has at least partially rebuilt four of these. One (Jokpo, located to the far west in the pasture lands of the Nyangdren Valley) is used as the base for its herds of yaks, and has been only minimally rebuilt. The other hermitages – the ones that do not belong to Sera today – were rebuilt by individuals, albeit with community support. Trashi Chöling was rebuilt by a devotee of Pabongkha Rinpoché, the previous lama-owner. Keutsang and Purchok were rebuilt by former monks of those hermitages, as were Garu and Negodong nunneries. Takten and Chupzang were slowly taken over by nuns with no formal prior affiliations to these institutions. They therefore became nunneries simply by virtue of the fact nuns gradually moved to these sites over the years.

A nun-meditator from Nenang Hermitage.

As one can see from the map, most of the hermitages survive to this day as Geluk institutions (either as monks’ hermitages or as nunneries). Of the nineteen12 original hermitages, all but two remain Geluk. Drakri (mixed nuns and Tantric priests, located in the far south), and Nenang (a nuns’ retreat center in the far northeast) are now Nyingma practice centers (drupdra).

Of the original nineteen hermitages, five are in ruins and have not been rebuilt. It is interesting that most of the hermitages that have not been rebuilt – Jokpo and Gönpasar in the far west, and Panglung and Khardo in the far northeast – lie farthest from Sera. New Keutsang is in fact the newly rebuilt version of Keutsang West, and so one can count Keutsang West as one of the hermitages that has been rebuilt (albeit not in exactly the same site as the original institution). Keutsang East (Keutsang Shar) belongs to Purchok Hermitage and lies in ruins. The monks of Purchok have decided to put their energies into the main Purchok hermitage rather than taking on the additional burden of rebuilding Keutsang East. With this one exception, then, the rule (just mentioned) applies: the closer a hermitage was to Sera, the greater its chances of being rebuilt.

History

A stylized painting of Purchok Hermitage as it existed before 1959. The deity shining rainbow light from the clouds onto the monastery is Byams Pa

Several of the hermitages have a history that predates the rise of the Geluk school. For example, Pabongkha, arguably the most important of all of the hermitages, is said to date to the imperial period. Nenang is said to have been a retreat site of Guru Rinpoché, and, if this is true, dates to the ninth century. Garu Nunnery (Garu Gönpa), founded by Pa Dampa Sanggyé (b. eleventh century), dates to the eleventh century, and Spangs lung, originally the meditation site of one of Pa Dampa Sanggyé’s students, to the early twelfth century. Of course, each of these sites was later taken over by Gelukpa monks, and so even when a site has a pre-Geluk history, it also has a Gelukpa “founder.”

Tsongkhapa (1357-1419), the founder of the Geluk school, is intimately connected to three hermitages – Sera Chöding, Sera Utsé, and Rakhadrak. Each of these are places where Tsongkhapa meditated, taught, and/or authored some of his most important works.13 So there is a sense in which Tsongkhapa “founded” these three hermitages in the fifteenth century, even if he himself probably had no notion of establishing formal institutions at these sites. And, indeed, there is no other founder of Chöding ever mentioned besides Tsongkhapa. But the tradition considers another later lama, Drupkhang Gelek Gyatso (1641-1713) to be the founder of the other two hermitages – Sera Utsé and Rakhadrak – at least qua monastic institutions. Two other hermitages were founded in the sixteenth century: Negodong Hermitage (Negodong Ritrö), founded by an eminent Sera scholar, Gomdé Namkha Gyeltsen; and Takten Hermitage (Takten Ritrö), founded by one of the most famous early meditators of the Geluk tradition, Ensapa Lozang Döndrup (1504/5-1565/6), who is often reckoned as the Third Penchen Lama (Penchen Kutreng Sumpa). One hermitage, Chupzang – founded by a monk who was a student (and regent) of the Fifth Dalai Lama (Dalai Lama Kutreng Ngapa, 1617-1682) as well as the uncle of his most famous regent, Desi Sanggyé Gyatso (1653-1705) – was established in the seventeenth century. But the remaining hermitages, eleven in all, were founded in the eighteenth century.

Why this spurt of hermitage-building in the eighteenth century? Why this passion for “taking to the hills” at this particular moment in time? Socio-economic and political factors may have played some role in monks’ decisions to leave Sera and seek the relative peace and quiet of the mountains. We know, for example, that by the late seventeenth century, Sera had a monastic population of close to 3,000 monks.14 While an intellectually stimulating atmosphere in which to pursue one’s studies, a monastery of this size is hardly the type of place that a monk with a contemplative bent would want to call home. Moreover, the eighteenth century saw a huge building boom at Sera. All three of Sera’s largest temples – the Sera Great Assembly Hall (Sera Tsokchen), the Jé College Assembly Hall (Jé Dukhang) as well as the Mé College Assembly Hall (Mé Dukhang) – were built between 1707 and 1761. This means that during these years monks would have had to put up with the chaos that comes from living in the midst of large-scale building projects. Nor is it inconceivable that junior monks, even if they were textualists, might have been conscripted to serve as laborers in these mammoth architectural undertakings.

![A detail of a painting of se ra from the eighteenth century depicting the monastery before all of the major temples had been constructed. The large (light blue) building in the rear of the monastery is undoubtedly the original se ra Assembly Hall (today the assembly hall of the Tantric College [sngags pa grwa tshang]). The three-story white building in the lower left may be what today is called the se ra theg chen khang gsar, a palace-like residence said to have been built by sde srid sangs rgyas rgya mtsho. This image is a detail of Item No. 65275 in the Collection of the Rubin Museum of Art, from the www.himalayanart.org website.](http://texts.thlib.org/essays/c/cabezon/hermintro-6.jpg)

A detail of a painting of Sera from the eighteenth century depicting the monastery before all of the major temples had been constructed. The large (light blue) building in the rear of the monastery is undoubtedly the original Sera Assembly Hall (today the assembly hall of the Tantric College [Ngakpa Dratsang]). The three-story white building in the lower left may be what today is called the Sera Tekchen Khangsar, a palace-like residence said to have been built by Desi Sanggyé Gyatso. This image is a detail of Item No. 65275 in the Collection of the Rubin Museum of Art, from the www.himalayanart.org website.

Political factors also might have played a role in the exodus of monks. With the growth of the Densa Sum – the three great Geluk seats of learning – there also came increased political power for these institutions. After the Fifth Dalai Lama’s consolidation of power in the middle of the seventeenth century, the seats of learning began to play an increasingly important role in Tibetan politics. While perhaps not as influential as Drepung – the seat of the Ganden Palace (Ganden Podrang), the headquarters of the Dalai Lama’s government – Sera, as the closest of the three seats of learning to Lhasa – also played a major role in the politics of the day. Sera monks, we know, took stances either in support of or opposition to the Qushot Mongolian chief, Lhazang Khang (d. 1717), in his successful bid to overthrow the Fifth Dalai Lama’s regent, Desi Sanggyé Gyatso, in 1705. For example, the then-abbot of the Mé College (Dratsang Mé) of Sera opposed Lhazang Khang, a position that he paid for with his life once the Qushot ruler came to power.15 But Lhazang Khang also rewarded the seats of learning financially when they supported him. At Sera, for example, he built the Great Assembly Hall, and he moved his personal ritual college into the old Sera assembly hall – today the site of the Sera Tantric College. In the same year that he had the Mé College abbot killed, he also gave to Sera the Drongmé estates that used to belong to the regent Sanggyé Gyatso.16

But Lhazang made some fatal political mistakes early in his rule. In the first year after assuming power he (or his wife) had the regent Sanggyé Gyatso beheaded. The following year Lhazang Khang sent the Sixth Dalai Lama (Dalai Lama Kutreng Drukpa, 1683-1706) into exile in Beijing (the Dalai Lama died on the way). Lhazang Khang also set up a puppet Dalai Lama, declaring him to be the true sixth Dalai Lama. Economically, opposition to Lhazang among the Kokonor (Tso Ngönpo) faction of the Qushots caused the latter to withhold donations to the great monasteries. This was financially devastating to the seats of learning, and it caused the Penchen Lama to send a mission to Kokonor in 1716 to try and reinstate Kokonor Qushot patronage of the great monasteries.17 All of these various moves cost Lhazang Khang the support of both the people and the seats of learning, and so when Dzungar Mongolian forces moved against him in 1717, promising to enthrone Kelzang Gyatso (1708-1757), a child from Litang, as the Seventh Dalai Lama (Dalai Lama Kutreng Dünpa), the seats of learning gave the Dzungars their support. They provided these rivals of the Qushots with monk soldiers and scouts who knew the terrain,18 and gave them provisions after their arrival on the outskirts of the city. Sera monks also joined the Dzungar troops as soldiers for the final push against Lhazang Khang.19 The Dzungars defeated the Qushots, but Dzungar rule would prove to be disastrous for Tibet. Even if the seats of learning were spared, the Dzungars sacked and looted Lhasa.20 They began to intervene in internal affairs of the seats of learning, purging what they considered to be the riffraff from the great monasteries.21 Far more serious, they destroyed many Nyingma monasteries, especially in southern Tibet, where they murdered scores of monks and sowed the seeds of bitter sectarian rivalries that would plague Tibet for most of its subsequent history.

The Chinese Manchu emperor – who had managed to protect the young Seventh Dalai Lama from being captured by the Dzungars in 1717 – saw Tibetans’ disillusionment with the Dzungars as an opportunity to weaken this powerful Mongol group that they had for some time perceived as a threat. The Manchus, therefore, decided to march on Lhasa with the young Dalai Lama (a crucial symbol of political legitimacy) in tow. Forming an alliance with several Qushot Mongol factions, and with pro-Qushot Tibetans – most notably Polhané (1689-1747), one of Lhazang’s former and most able commanders – they entered Lhasa in 1720, overthrew the Dzungars, and enthroned the young Kelzang Gyatso as the Seventh Dalai Lama. They also took this opportunity to purge the seats of learning of Dzungar influence by expelling all Dzungar lamas from the great monasteries.22

Polhané (right), and his son (left): detail of a mural in one of the regional houses (khangtsen) of Sera (Tibet). |  The remains of one of Tibet’s great kings, Polhané, are said to rest inside this funerary stūpa on the main altar in the Jé College Assembly Hall. |

A series of events initiated by the death of the Manchu Kangxi (Kangshi, 1654-1722) emperor in 1722 destabilized the delicate political balance in Lhasa yet again. However, by 1729 Polhané had, with Manchu backing, managed to consolidate power. He ruled for eighteen years and, like his original Qushot mentor Lhazang Khang, he was a great patron of the Geluk seats of learning. At Sera, he is chiefly known as the individual who provided the funds for the building of the Jé College Assembly Hall.23 His funerary stūpa is housed on the main altar of that very building.

As we can see from this brief historical overview, the first half of the eighteenth century was an exceedingly turbulent period in Tibetan history. Sera, it is clear, was a major player in the power-politics of the day. Was Sera’s involvement in the political machinations and power struggles during the first half of the eighteenth century at all related to the establishment of the hermitages? We cannot say for sure, but it is hardly a major leap to conclude that monks with a more contemplative calling – monks who wished to remain aloof from political intrigues in order to pursue study and meditation – might have chosen to avoid an institution like Sera. Or else they might have chosen to enter for a limited time to pursue their studies, but then quickly to exit. And this is in fact what several of the founders of the Sera hermitages did at this precise time.

Socio-demographic factors (such as the size of Sera and its physical expansion), and political factors (such as Sera’s increasing involvement in the chaotic politics of the day) might have been contributing factors to the founding of the hermitages, but one cannot reduce the rise of the hermitage movement to these factors alone. Clearly, religious motivations were at work as well. If the number of hermitages founded during a given period is any indication of a generation’s desire for meditation and isolated retreat, then the eighteenth century must be considered one of the most “contemplative” centuries in the history of the Geluk school, or at least in the history of Sera. It seems likely that the exodus into the mountains at this time was in large part the result of the influence of one charismatic figure, the great meditator and scholar Drupkhang Gelek Gyatso. Drupkhangpa is so important to the history of the Sera hermitage tradition that it behooves us to say a bit more about him.24

A detail of an eighteenth-century painting in the collection of the Rubin Museum of Art (Image no. 105 on the www.himalayanart.org website) identified as Drupkhangpa

Drupkhangpa was born in Zangskar (Zangkar) in 1641. His father died when he was six years old, and he spent most of his youth caring for his sick mother. His mother passed away when he was 17, and it was at this point that he began his religious career. He spent two years at the monastery of Jampa Ling, and then, at the age of nineteen, he set out for central Tibet to further his studies. On his way, he took novice monastic ordination from Drungpa Tsöndrü Gyeltsen (fl. seventeenth century), a student of one of the most important figures in the history of Sera, Khöntön Peljor Lhündrup (1561-1637). Drupkhang Gelek Gyatso then went to Sera. We do not know why his stay there was so short, but he quickly left Sera and enrolled instead at the Dakpo College (Dakpo Dratsang), where he remained for sixteen years. He returned to Drungpa Rinpoché to take full ordination. After Drungpa Tsöndrü Gyeltsen’s death, Drupkhangpa continued his studies at Trashi Lhünpo with some of Drungpa Rinpoché’s students. After a couple of years there, he returned to Sera, where he became a student of the abbot of the Jé College, Jotön Sönam Gyeltsen (seventeenth century). He left Sera sometime shortly after 169225 to begin a series of pilgrimages and meditation retreats in important sites throughout central and southern Tibet.26 He returned to the Sera foothills some thirteen years later, in 1705. It was at this time, it seems, that he founded three hermitages:

- Purchok, where he built the famous Temple of the Three Protectors (Riksum Gönpo Lhakhang). He entrusted this institution to his student, Ngawang Jampa (1682-1762). Tradition has it that Drupkhangpa established Purchok with one-hundred monks.

- Rakhadrak, established with twelve fully-ordained monks, and

- Sera Utsé, established with seventeen fully-ordained monks. He made this latter hermitage his home.

Drupkhangpa influenced several important young scholar-meditators of his day. Purchok Ngawang Jampa we have already mentioned. This influential figure gained a reputation as a brilliant scholar at a very young age. But he also had a passion for meditation, which is obviously what led him to seek out Drupkhangpa as his teacher. It appears that they first met in 1699, but it was not until Ngawang Jampa had finished his studies in 1707 that he began to study intensively with Drupkhangpa. Under Drupkhangpa’s supervision he remained at Purchok Hermitage in meditation for many years. Later in life he was called to public service, most notably as the tutor to the Eighth Dalai Lama Jampel Gyatso (Dalai Lama Kutreng Gyépa Jampel Gyatso, 1758-1804). Purchok Ngawang Jampa is credited in one source with being the founder of another hermitage, Keutsang East. He also influenced other figures in the hermitage tradition: for example, Longdöl Lama Ngawang Lozang (1719-1794), and Yongdzin Yeshé Gyeltsen (1713-1793),27 who founded Tsechokling at the opposite (southern) end of the Lhasa Valley.

A statue of Purchok Ngawang Jampa, located in the cave in which he first meditated at Purchok, a hermitage that he co-founded with his teacher Drupkhangpa. |  A detail of a painting in the collection of the Rubin Museum of Art (Image no. 105 in the www.himalayanart.org website) identified as Khardo Zöpa Gyatso (1672-1749). |

Another student of Drupkhangpa, Khardo Zöpa Gyatso, also known as Lozang Gomchung, was responsible for founding the Khardo Hermitage on the mountainside across the road from Purchok.28 Khardo Zöpa Gyatso was born near Lhasa in 1672. He entered the Jé College of Sera when he was thirteen years old and studied all of the major scholastic subjects under the Jé Khenpo Gyeltsen Döndrup (seventeenth century). At age twenty, Khardowa took full ordination under this same teacher and then spent the next several years in retreat in different locations in central and southern Tibet. It was during this time that he perfected different alchemical techniques for extracting nutritive powers from water, pebbles, and flowers.29 In 1706 he came back to Lhasa with the few students that he had gathered in his travels. It was perhaps at this time that he apprenticed himself to Drupkhangpa.30 In any case, we know that it was shortly after his return to Lhasa that Khardowa settled on a bluff at the far northwestern end of the Lhasa Valley, across from Purchok, where he began to build a hermitage, and to teach extensively. He continued to travel intermittently even after he had founded his small hermitage, gathering many students from different parts of Tibet.

Khardo Hermitage came to be the dominant force in Dodé (the area northeast of Lhasa). At some point in time, the Khardo Hermitage assumed responsibility for the small hermitage of Negodong that was located just beneath it at the foot of the mountain near the village of Dodé. And in the mid-nineteenth century, the third Khardo Lama, Chökyi Dorjé (b. eighteenth century?), built Nenang Nunnery at the far end of the Dodé Valley. These three hermitages – Negodong, Nenang, and Khardo itself – came to be known together as “the three practice centers of Khardo” (Khardo Drupdé Sum).

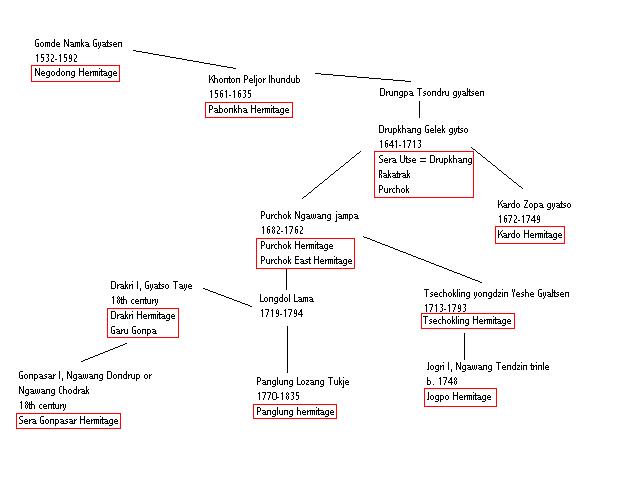

To summarize, seven of the nine hermitages to the east of Sera were founded either by Drupkhang Gelek Gyatso or by one of his direct disciples in the eighteenth century. Panglung Hermitage, just behind Purchok, was founded by one of Drupkhangpa’s great-grand-students, Panglung Kutreng Dangpo Lozang Tukjé (1770-ca. 1835).31 The chart that follows traces the teacher-student relationships between some of the figures we have mentioned so far.

|

The building of hermitages in the environs of Sera comes to a halt around the end of the eighteenth century. After the beginning of the nineteenth century no new hermitages were built. Why? Although we cannot answer with absolute certainty, we can speculate as to the reasons. One possibility is that a kind of saturation point had been reached. Hermitage building always required the permission of the Ganden Palace (the Tibetan government), and it usually required the endowment of these institutions with estates. It is not inconceivable that the government felt that a limit had been reached as regards its ability to provide for these institutions through estate endowments. Or perhaps the government felt that it was putting undue burden on the local populace, which was obligated (morally, if not legally) to further subsidize the hermitages with donations. It is also not inconceivable that the Sera administration might itself have protested the building of new hermitages, since the seats of learning were institutions that competed with the hermitages both for donors and for monks. A second possibility is that, given the relative political stability of the seats of learning from the mid eighteenth century, fewer monks felt the need to leave Sera, making the building of new hermitages unnecessary. Third, perhaps monastic life in the seats of learning became so normalized and idealized that the isolated contemplative life of the solitary yogi was no longer as valued (or as encouraged) as it had been in earlier days. Finally, is not inconceivable that senior monks of Sera dissuaded their more promising students from going into isolated life-long retreat, encouraging them instead to either enter the Tantric Colleges, thereby launching them on the process of ascending through the stages of the Geluk hierarchy, or else to remain as teachers at Sera, where there was always a demand for good textualists. Or perhaps it was a combination of all of these factors that brought an end to the founding of new hermitages.

Not only did hermitage-building cease, but the hermitages that already existed underwent a fairly radical transformation at the end of the eighteenth century. Within one or two generations of their founding, all of the hermitages became prototypical ritual monasteries – that is, monasteries where ritual (choga chaklen, zhapten), rather than, say, individual meditation on the graded stages of the path (lamrim) and on the tantras, was the principal activity of the monks and nuns. True, some hermitages kept a few meditation huts for monks who wanted to do individual retreat, but even those institutions that made room for contemplatives in their ranks transformed into monasteries where the primary focus was ritual. Why did this happen?

The original hermitages began as meditation retreat centers. But to thrive as a meditation retreat center an institution requires the leadership of a charismatic contemplative. Almost all of the founders of the hermitages had this type of drive and charisma. Once these founding figures had passed away, however, the leadership of the hermitages passed on not to a senior student (who might also have had this same vision), but rather to the next incarnation of the founding lama. These later incarnations were rarely as committed to the contemplative life as were their predecessors. There were several reasons for this. The young incarnations (trülku) – or lamas, as they are called in the seats of learning – were given official status at Sera.32 As lamas they were expected to enter Sera for their studies, where they were then enculturated from a very early age into the life of the seat of learning and into its ethos. Wherever the yearning for a contemplative life comes from, it does not generally come as the intentional product of seat of learning life. Put another way, the goal of the seats of learning was not to produce hermits and meditators, but to create scholars who were the embodiments of the Geluk tradition: to fashion monks who exemplified the teachings of Tsongkhapa through their learning, comportment, and ritual skills. Young lamas learned this lesson well, and they almost never rejected this ideal in favor of the life of the solitary yogi. This is not to say that the life of the solitary meditator-yogi was not (and is not) an ideal among the Gelukpas (Tsongkhapa, after all, was precisely this for much of his life), nor is it to deny that many lamas also might have had such an inclination. But even those lamas who had a yearning for the hermit’s life would have found it difficult to live out this calling by renouncing their position and heading to the mountains, for once a young boy had been identified as the leader of a now-institutionalized hermitage, there were a variety of forces and interests to keep him in this position. For example, the lama’s household (or lama’s estate) depended on the physical presence of the lama for its fiscal survival, and the hermitage, in turn, depended on the lama’s estate for its financial stability. In brief, there were many reasons – sociological, economic, and even political – that caused the subsequent incarnations of the hermitages’ founders not to be as committed to the kind of contemplative lives that their predecessors had led. Lacking the contemplative charismatic leadership of the original founders, it is not surprising that the institutions headed by these individuals also changed. But change into what? There was no need for the hermitages to transform into educational institutions. The seats of learning already had a monopoly in this sphere, and the smaller monasteries near an institution like Sera could not have competed with the seats of learning when it came to providing monks with a textual education. This left only one other option: ritual. In the absence of leaders with contemplative charisma, the only option for the hermitages was to transform into institutions whose primary focus was communal ritual. And this is in fact what happened.

Perhaps the historical lesson here is a simple one: hermitages (or, to be more specific, Geluk hermitages near the seats of learning) do not stay isolated, meditation-oriented institutions for long. The centripetal pressure to grow, and the centrifugal pressure to institutionalize, to become part of the Geluk establishment and to become affiliated to larger and more powerful institutions like the seats of learning is simply too great for these establishments to remain small, independent, and contemplatively-driven for very long. With their transformation into ritual institutions, the hermitages were, of course, no longer the classical “solitary sites” (ené) sought out by yogis. And just as the founders of the hermitages had to leave Sera for the mountains around the monastery in order to pursue their contemplative vocation in the eighteenth century, latter-day yogis would have to leave not only Sera but also the hermitages. At least this is what they would have to do if their goal was to meditate in relative isolation and without the responsibilities that come from being a member of a ritual monastery.

After the events of 1959, the hermitages were all forcibly shut down and fell into disrepair. Monks and nuns started rebuilding them after the liberalization of the 1980s. Most of the hermitages were rebuilt in the 1990s. Initially, the local Lhasa government was fairly generous in granting permits to rebuild these institutions. In the last few years, however, it has been close to impossible to get permission to rebuild – and, indeed, even to add new structures to already rebuilt hermitages or to make modifications to existing buildings. The attitude in the Lhasa bureaucracy today is more stringent in part because of the prevailing attitude among government bureaucrats that there are already too many monks and nuns in and around Lhasa. (This is not surprising, given that monastics have been very vocal in protesting the Chinese occupation of Tibet over the last two decades.) Hence, there are restrictions not only on rebuilding and renovation, but also on the number of monks and nuns that can live in the hermitages. As a result, those five hermitages that have not already been rebuilt will probably never be rebuilt. As the elder monks who knew the traditions of these institutions pass away, these institutions, like so much of Tibet’s rich religious culture, will disappear from cultural memory just as they are physically disappearing from the landscape of Lhasa.

But let us end on a less gloomy note. It is a great irony that, in the wake of the destruction of the hermitages, some of these sites are once again becoming retreat centers for meditators. This is not to say that the newly renovated hermitages have renounced their focus on ritual. They have not. Rather, it is the ruins and caves of the hermitages that have not been renovated that are serving as homes for contemporary yogis (mainly nuns). For example, nuns have settled at Nenang and Khardo, transforming these ruins into meditation retreat centers – which is to say, into the types of places that their founders originally intended them to be. The phoenix rising out of the ashes of its own burnt body comes to mind as an appropriate metaphor for this phenomenon.

Life in the Sera/Se ra Hermitages

By 1959, almost all of Sera’s hermitages had been ritual institutions for close to two-hundred years. If a monk who had entered a hermitage wanted to study, he would go to Sera. If he wanted to do life-long, isolated meditation retreat, he would seek a truly secluded place in the mountains. By the same token, if a Sera monk did not want to study, and if he was content to lead the life of a ritualist, he could enter a hermitage (if permitted by his regional house and accepted by the hermitage). Of course, a monk who wanted to lead the life of a ritualist could remain at Sera, but life in a hermitage was often much easier than life in a seat of learning, especially if the hermitage was the seat of a high lama who was wealthy. Be that as it may, those monks who entered the hermitages knew the type of life they would be living. They would either be engaged in ritual (especially if they had a good voice or knew how to play a musical instrument), or they would serve as support staff for the hermitage: cleaning, tending altars, cooking, doing business on the hermitage’s behalf, or supervising one of its estates.

To become an official monk or nun in one of the hermitages the postulant would have to submit to an examination (gyuk). By the time monks and nuns were senior members of the institution, they would have memorized close to five-hundred pages of ritual texts.33 Monks and nuns performed the rituals of the hermitage in monthly and yearly ritual cycles in accordance with the institution’s liturgical calendar. If no sponsor was available, the fixed rituals would be “paid for” by the hermitage itself. That is, the monastery would provide the monks and nuns with food (often better than the day-to-day fare) for the duration of the ritual cycle. But local lay people, monks from other monasteries, and the Tibetan government often commissioned rituals – sometimes acting as sponsors for one of the monastery’s own fixed ritual cycles, sometimes requesting the hermitage to perform special rituals on one of its free days. There were, of course, plenty of lay people in the Lhasa Valley and its suburbs who needed such rituals (zhapten) to be performed on their behalf. On occasion, a small group of monks or nuns from the hermitage might also be invited to a lay person’s home to do ritual there. Rituals have always been an important source of income for the hermitages and for their individual monks and nuns.

While there is some variation in the monthly and yearly liturgical cycles of the hermitages, there is also a great deal of overlap. Almost all of the hermitages, for example, celebrate the new and full moon days,34 as well as the tenth and twenty-fifth of the lunar month. Some of them also perform protector deity practices on an additional day every month.

There is also a great deal of similarity in the yearly ritual cycle. Monks and nuns perform quite extensive multiple-day ritual cycles during the New Year (Losar), and during the “Sixth-Month Fourth-Day” (Drukpa Tsezhi) celebrations. This latter holiday, also called “Festival of the Turning of the Wheel of the Doctrine” (Chönkhor Düchen), is a major pilgrimage day for Tibetans from Lhasa and surrounding areas, as thousands of people travel along a route in the foothills above Sera from Pabongkha Hermitage in the west to Purchok in the east. A good deal of the hermitages’ income for the year derives from the moneys and in-kind goods collected in the form of offerings on this day (at least if the hermitage is fortunate enough to lie on the pilgrimage circuit). At different times of the year (in the first fortnight of the fourth Tibetan month, for example) the hermitages also perform two-day Avalokiteśvara fasting ritual (nyungné) – often doing multiple sets of two-day rituals consecutively.35 The hermitages also, of course, celebrate other major pan-sectarian holidays, like the Buddha’s birth/death date, as well as Geluk-specific holy days like the commemoration of Tsongkhapa’s death – the Ganden Feast of the 25th (Ganden Ngamchö) – that takes place on the twenty-fifth day of the twelfth Tibetan month. All of the hermitages, it seems, also maintained the “rainy-season retreat” (yarné) tradition, during which monks and nuns minimize their movement for a portion of the summer so as to avoid killing insects that are more prevalent on the ground during this time.

Nuns perform a Medicine Buddha (Menla) ritual for a benefactor at Negodong nunnery |  Detail of a tangka of Nyang bran rgyal chen preserved in one of the regional houses of Sera, India. |

Of course, each hermitage has its own set of tutelary deities (yidam) and protector deities (sungma, chökyong), and so the rites performed by the monks and nuns may vary from one monastery to the next. But given that all of them are Geluk institutions, there is also a great deal of overlap in the deities propitiated, and in the actual liturgies performed. Hence, for example, many of the monasteries perform the self-generation (dakkyé) and self-initiation (danjuk) rituals of Vajrabhairava, and they propitiate protector deities like Penden Lhamo, Mahākāla (Gönpo), Dharmarāja (Chögyel), and Vaiśravana (Namsé). In some monasteries, especially in the hermitages to the west of Sera, the protector Nyangdren Gyelchen, the local site-protector of the Nyangdren Valley, is also propitiated. The rites written by Pabongkha Dechen Nyingpo (1878-1941) continue to be as popular today as they were before 1959.

As an example, here are the principal ritual practices done at one of the hermitages, Garu Nunnery, in a one-month period (the dates given are the dates in the Tibetan lunar month):

| Date | Ritual Practice (Tibetan) | Ritual Practice (English) |

| 8 | Drölchok (Sgrol chog) Tungshak (Ltung bshags) | Tārā Ritual36 The Ritual of the Thirty-Five Confession Buddhas |

| 10 | Demchok Lachö (bde mchog bla mchod) Jikjé Danjuk (’Jigs byed bdag ’jug)37 | Offering to the Master Based on the Deity Cakrasaṃvara Self-Initiation of Vajrabhairava |

| 15 | Menla Deshek Gyé (sman bla bde gshegs brgyad)38 | Ritual of the Eight Medicine Buddhas |

| 1939 | Gönpo Chögyel Lhamo Namsé dang Nyangdren Gyelchengyi Kangsol (mgon po/ chos rgyal/ lha mo/ rnam sras dang/ nyang bran rgyal chen gyi bskang gsol) | Propitiation Rituals of Mahākāla, Dharmarāja, Vaiśravana, Penden Lhamo, and Nyangdren Gyelchen |

| 25 | Demchok Lachö (bde mchog bla mchod)40 Neljormé Danjuk (rnal ’byor ma’i bdag ’jug) | Offering to the Master Based on the Deity Cakrasaṃvara Self-Initiation of Vajrayoginī |

| 30 | Neten Chudruk (gnas brtan bcu drug)41 | The Sixteen Arhats Ritual |

In addition to performing rituals, the monks of the male hermitages have traditionally seen it as part of their duties to keep a number of rooms open for visiting Sera monks. Textualists or pechawa from Sera’s two philosophical colleges – Jé and Mé – had a number of study breaks between the different study periods,42 and they would often seek the relative peace and quiet of the hermitages, usually not for meditation, but for intensive memorization retreats. This tradition still exists, although today the monks tend to request rooms in the hermitages owned by (and closest to) Sera rather than seeking rooms in privately-held hermitages like Purchok. Sera Utsé, Sera Chöding, and Rakhadrak have always been especially popular with Sera monks who want to do such retreats not only because of their proximity to Sera, but also because of the strong associations of these three hermitages with events in the life of Tsongkhapa.

A Sera monk who in 2004 was engaged in a textual retreat (petsam) at Rakhadrak Hermitage. He is occupying a room adjacent to the cave of Tsongkhapa.

As with many monasteries in Tibet today, the population of the Sera hermitages is quite young. The vast majority of the monks and nuns are under the age of thirty, and many are much younger. While the nunneries appear to be thriving, the fate of the male hermitages is not as clear. In pre-1959 Tibet, there were basically only two career options available to young men and women: they either became monks and nuns, or they chose a family life. If they chose the latter and they entered the workforce, they usually followed in the footsteps of their parents, who were either farmers (zhingpa), nomads (drokpa),43 or, less frequently, merchants (tsongpa). The life of the farmer and nomad was a difficult life. By comparison, the monastic life was more secure, and it provided opportunities for education – and therefore for social and economic advancement – that were not normally available to ordinary villagers and nomads.

Today the situation is quite different. Young men and women have (at least in theory) more choices open to them. Secular education (almost exclusively in the medium of Chinese language) is now a possibility, even if it is still mostly accessible only to the middle and upper classes in urban areas. And there are a variety of career options that were not available before 1959 (mostly for those who are educated and who live in, or who relocate to, larger urban areas). How much opportunity actually exists for Tibetan youths – as important as this question is – is not really the issue we are concerned with here. Rather, what is most important for us as we contemplate the future of institutions like the hermitages is the perception that exists in the minds of young Tibetans about their possible future. In their minds, driven in large part by the visions they absorb from television and films, the world is filled with opportunities, life-choices and lifes that compete with the monastic life. But Tibetans are an extremely devout people, and monks and nuns continue to enter the monasteries and nunneries, often with a great sense of religious calling, and with an idealistic vision of what it will be like to live in such an institution. This influx of young Tibetans into small monasteries like the hermitages is not something that one sees changing anytime in the near future. What is changing is what happens after young people (and especially young men) enter monasteries. And here the pattern seems to be that most of the young monks leave the monastery before they are twenty years of age. The problem for the hermitages, then, is not one of recruitment but of retention.44 At least this is the problem in smaller monasteries, and especially in smaller monasteries near a large cosmopolitan area like Lhasa, where, because of its physical proximity, the secular and modern life entices young monks with even greater force.45

An elder monk from one of the hermitages complained to me, for example, that he had “lost” many young boys in their late teens, and that he was considering not accepting boys any longer, his theory being that if one holds out for more mature young men in their twenties (preferably already ordained), one is more apt to get candidates who already know what is in store for them, and who will not be so easily enticed by the lures of the world. It remains to be seen, however, how many monks there are who fit this description and are not already committed to another monastic institution. Or, if such individuals do exist, it remains to be seen how many of them see themselves living out their lives in a relatively isolated, small, ritual monastery. If it is impossible to lure such monks to the hermitages, then the administrators of these institutions may have to resign themselves to the fact that their monasteries will be, for all intents and purposes, something akin to religious boarding schools for young men, the majority of whom will most likely leave once they reach their twenties. But even if they leave, perhaps these young men will return to the hermitages at the end of their life, to live out their final years in a religious setting, a pattern that we have seen in other Tibetan contexts.46 Be that as it may, one thing is clear: life in the hermitages is different from what it was before 1959, and the problems that hermitages face today are as much due to global and market forces as they are to Chinese Communist ideology and bureaucratic regulation.

Glossary

Note: The glossary is organized into sections according to the main language of each entry. The first section contains Tibetan words organized in Tibetan alphabetical order. To jump to the entries that begin with a particular Tibetan root letter, click on that letter below. Columns of information for all entries are listed in this order: THL Extended Wylie transliteration of the term, THL Phonetic rendering of the term, the English translation, the Sanskrit equivalent, associated dates, and the type of term. To view the glossary sorted by any one of these rubrics, click on the corresponding label (such as “Phonetics”) at the top of its column.

| Ka | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ka thung | katung | short pillar | Term | ||

| ka ring | karing | long pillar | Term | ||

| kang shi | Kangshi | Kangxi | 1654-1722 | Person | |

| kun rig rnam par snang mdzad | Künrik Nampar Nangdzé | Sarvavid Vairocana | Buddha | ||

| ke’u tshang | Keutsang | Monastery | |||

| ke’u tshang | keutsang | cave, cavern, or overhang | Term | ||

| ke’u tshang sku phreng lnga pa | Keutsang Kutreng Ngapa | the fifth Keutsang incarnation | Person | ||

| ke’u tshang sku phreng gnyis pa | Keutsang Kutreng Nyipa | the second Keutsang incarnation | b. 1791 | Person | |

| ke’u tshang sku phreng gnyis pa blo bzang ’jam dbyangs smon lam | Keutsang Kutreng Nyipa Lozang Jamyang Mönlam | the second Keutsang incarnation Lozang Jamyang Mönlam | b. 1791 | Person | |

| ke’u tshang sku phreng dang po byams pa smon lam | Keutsang Kutreng Dangpo Jampa Mönlam | the first Keutsang incarnation Jampa Mönlam | d. 1790 | Person | |

| ke’u tshang ’jam dbyangs blo gsal | Keutsang Jamyang Losel | Person | |||

| ke’u tshang nub | Keutsang Nup | Keutsang West | Monastery | ||

| ke’u tshang nub ri khrod | Keutsang Nup Ritrö | Keutsang West Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| ke’u tshang sprul sku | Keutsang Trülku | Keutsang incarnation | Person | ||

| ke’u tshang bla brang | Keutsang Labrang | Keutsang Lama’s estate | Monastery | ||

| ke’u tshang bla ma | Keutsang Lama | Person | |||

| ke’u tshang ri khrod | Keutsang Ritrö | Keutsang Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| ke’u tshang shar | Keutsang Shar | Keutsang East | Monastery | ||

| ke’u tshang shar ri khrod | Keutsang Shar Ritrö | Keutsang East Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| kong po jo rdzong | Kongpo Jodzong | Place | |||

| krung go’i bod rig pa dpe skrun khang | Trunggö Börikpa Petrünkhang | Publisher | |||

| klong rdol bla ma ngag dbang blo bzang | Longdöl Lama Ngawang Lozang | 1719-1794 | Person | ||

| dkar chag | karchak | inventory | Term | ||

| dkar chag | karchak | catalogue | Term | ||

| bka’ ’gyur | Kangyur | Scriptures | Tibetan text collection | ||

| bka’ ’gyur lha khang | Kangyur lhakhang | Scripture Temple | Building | ||

| bka’ brgyud | Kargyü | Organization | |||

| bka’ gdams pa | Kadampa | Organization | |||

| bka’ gdams lha khang | Kadam Lhakhang | Kadam Chapel | Room | ||

| bka’ babs bu chen brgyad | kabap buchen gyé | eight great close disciples | Term | ||

| bka’ babs ming can brgyad | Kabap Mingchen Gyé | the “eight great ones who were named to receive the oral instructions” | |||

| bkra shis chos gling | Trashi Chöling | Monastery | |||

| bkra shis chos gling ri khrod | Trashi Chöling Ritrö | Trashi Chöling Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| bkra shis gser nya | trashi sernya | two auspicious golden fish | Term | ||

| bkra shis lhun po | Trashi Lhünpo | Monastery | |||

| sku mkhar | kukhar | castle | Term | ||

| sku mkhar ma ru | Kukhar Maru | Maru Castle | Building | ||

| sku bzhi khang | Kuzhi Khang | Chapel of the Four Statues | Room | ||

| sku rim grwa tshang | kurim dratsang | ritual college | Term | ||

| bskang gso | kangso | propitiation ritual | Ritual | ||

| bskal bzang rgya mtsho | Kelzang Gyatso | 1708-1757 | Person | ||

| Kha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| khang tshan | khangtsen | regional house | Term | ||

| khams | Kham | Place | |||

| khal | khel | a unit of weight/volume equal to about 25-30 lbs. | Term | ||

| khri byang sku phreng gsum pa blo bzang ye shes | Trijang Kutreng Sumpa Lozang Yeshé | the third Trijang incarnation Lozang Yeshé | 1901-1981 | Person | |

| khri byang rin po che | Trijang Rinpoché | 1901-1981 | Person | ||

| khrod | trö | in the midst of | Term | ||

| khrod | trö | on the side of | Term | ||

| mkhan ngag dbang bstan ’dzin | Khen Ngawang Tendzin | Person | |||

| mkha’ spyod dbyings | Khachö Ying | Room | |||

| mkhar rdo | Khardo | Monastery | |||

| mkhar rdo sku phreng lnga pa jam dbyangs chos kyi dbang phyug | Khardo Kutreng Ngapa Jamyang Chökyi Wangchuk | the fifth Khardo incarnation Jamyang Chökyi Wangchuk | 19th-20th centuries | Person | |

| mkhar rdo sku phreng drug pa ’jam dpal thub bstan nyan grags rgya mtsho | Khardo Kutreng Drukpa Jampel Tupten Nyendrak Gyatso | the sixth Khardo incarnation Jampel Tupten Nyendrak Gyatso | 1909/12?-1956? | Person | |

| mkhar rdo sku phreng bdun pa ’jam dpal bstan ’dzin nyan grags rgya mtsho | Khardo Kutreng Dünpa Jampel Tendzin Nyendrak Gyatso | the seventh Khardo incarnation Jampel Tendzin Nyendrak Gyatso | Person | ||

| mkhar rdo sku phreng bzhi pa padma dga’ ba’i rdo rje | Khardo Kutreng Zhipa Pema Gawé Dorjé | the fourth Khardo incarnation Pema Gawé Dorjé | 19th century | Person | |

| mkhar rdo sku phreng gsum pa chos kyi rdo rje | Khardo Kutreng Sumpa Chökyi Dorjé | the third Khardo incarnation Chökyi Dorjé | b. 18th century | Person | |

| mkhar rdo sku phreng gsum pa rigs ’dzin chos kyi rdo rje | Khardo Kutreng Sumpa Rikdzin Chökyi Dorjé | the third Khardo incarnation Rikdzin Chökyi Dorjé | Person | ||

| mkhar rdo mthun mchod | Khardo Tünchö | Festival | |||

| mkhar rdo ba | Khardowa | Person | |||

| mkhar rdo bla brang | Khardo Labrang | Khardo Lama’s estate | Organization | ||

| mkhar rdo tshoms chen | Khardo Tsomchen | Khardo Assembly Hall | Room | ||

| mkhar rdo ri khrod | Khardo Ritrö | Khardo Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| mkhar rdo rin po che | Khardo Rinpoché | Person | |||

| mkhar rdo srong btsan | Khardo Songtsen | Buddha | |||

| mkhar rdo sgrub sde gsum | Khardo Drupdé Sum | the three practice centers of kardo | Monastery | ||

| mkhar rdo ba | Khardowa | Person | |||

| mkhar rdo bla ma | Khardo Lama | Person | |||

| mkhar rdo bzod pa rgya mtsho | Khardo Zöpa Gyatso | 1672-1749 | Person | ||

| mkhar rdo gshin rje ’khrul ’khor | Khardo Shinjé Trülkhor | Khardo (Hermitage’s) Lord of Death Machine | Term | ||

| mkhas grub rje | Kedrupjé | 1385-1438 | Person | ||

| ’khon ston | Khöntön | 1561-1637 | Person | ||

| ’khon ston dpal ’byor lhun grub | Khöntön Peljor Lhündrup | 1561-1637 | Person | ||

| ’khrungs dbu rtse | Trung Utsé | Birth Peak | Place | ||

| ’khrungs ba’i bla ri | Trungwé Lari | Birth Soul Mountain | Place | ||

| ’khrungs ba’i lha ri | Trungwé Lhari | Birth Deity Peak | Place | ||

| Ga | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| ga ru | Garu | Monastery | |||

| ga ru | Garu | dance | Term | ||

| ga ru dgon pa | Garu Gönpa | Garu Nunnery | Monastery | ||

| gar | gar | dance | Term | ||

| gar dgon bsam gtan gling | Gargön Samten Ling | Dance Gompa: Place of Meditative Equipoise | Monastery | ||

| gar dgon bsam gtan gling gi lo rgyus mun sel mthong ba don ldan | Gargön Samten Linggi Logyü Münsel Tongwa Dönden | A History of Gargön Samten Ling: Clearing Away Darkness, Meaningful to Behold | Tibetan text title | ||

| gar lo | Garlo | A History of Garu [Nunnery] | Tibetan text title | ||

| gu ru rin po che | Guru Rinpoché | 8th century | Person | ||

| grub thob lha khang | Druptop Lhakhang | Siddha Chapel | Room | ||

| grog mo chu mig | Drokmo Chumik | Ravine Spring | Place | ||

| grong smad | Drongmé | Place | |||

| grwa tshang byes | Dratsang Jé | Jé College | Monastery | ||

| grwa tshang smad | Dratsang Mé | Mé College | Monastery | ||

| grwa bzhi | Drapchi | Building | |||

| grwa bzhi lha khang | Drapchi Lhakhang | Drapchi Temple | Building | ||

| glang dar ma | Langdarma | d. 842 | Person | ||

| dga’ chos dbyings | Gachö Ying | Room | |||

| dga’ ldan | Ganden | Monastery | |||

| dga’ ldan khri pa | Ganden tripa | throne-holder of Ganden | Term | ||

| dga’ ldan lnga mchod | Ganden Ngamchö | the Ganden Feast of the 25th | Festival | ||

| dga ldan chos ’nyung bai ḍūrya ser po | Ganden Chönyung Baidurya Serpo | Yellow Lapis: A History of the Ganden [School] | Tibetan text title | ||

| dga’ ldan pho brang | Ganden Podrang | Ganden Palace | Organization | ||

| dga’ spyod dbyings | Gachö Ying | Room | |||

| dgun nyi ldog gi cho ga | Gün Nyidokgi Choga | Winter Solstice Ritual | Ritual | ||

| dge lugs | Geluk | Organization | |||

| dge lugs pa | Gelukpa | Organization | |||

| dge bshes | geshé | Term | |||

| dge bshes pha bong khar grags pa | Geshé Pabongkhar drakpa | “Geshé Pabongkha” | Person | ||

| dge bshes brag dkar ba | Geshé Drakkarwa | 1032-1111 | Person | ||

| dge bshes ye shes dbang phyug | Geshé Yeshé Wangchuk | b. 20th century | Person | ||

| dge bshes seng ge | Geshé Senggé | d. 1990s | Person | ||

| dge slong | gelong | fully-ordained monk | Term | ||

| dgon pa | gönpa | monastery | Term | ||

| dgon pa gsar | Gönpasar | Monastery | |||

| dgon pa gsar | gönpa sar | new monastery | Term | ||

| dgon pa gsar sku phreng dang po ngag dbang don grub | Gönpasar Kutreng Dangpo Ngawang Döndrup | first Gönpasar incarnation Ngawang Döndrup | 18th century | Person | |

| dgon pa gsar ri khrod | Gönpasar Ritrö | Gönpasar Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| mgon dkar | Gönkar | White Mahākāla | Buddha | ||

| mgon khang | gönkhang | protector deity chapel | Term | ||

| mgon po | Gönpo | Mahākāla | Buddha | ||

| mgon po gtor rgyag | Gönpo Torgyak | Throwing of the Torma to Mahākāla | Ritual | ||

| mgon po phyag drug | Gönpo Chakdruk | Six-Armed Mahākāla | Buddha | ||

| mgon po a gho | Gönpo Agho | Buddha | |||

| ’gyed | gep | money offering to monks | Term | ||

| rgya mtsho mtha’ yas | Gyatso Tayé | Person | |||

| rgya res | Gyaré | Buddha | |||

| rgya res tshoms chen | Gyaré Tsomchen | Building | |||

| rgyal chen karma ’phrin las | Gyelchen Karma Trinlé | Buddha | |||

| rgyal ba lnga pa chen po | Gyelwa Ngapa Chenpo | the Great Fifth Dalai Lama | 1617-1682 | Person | |

| rgyal ba’i rigs lnga bla ri | Gyelwé Riknga Lari | Soul Mountain of the Buddhas of the Five Families | Place | ||

| rgyal mo tshe ring bkra shis | Gyelmo Tsering Trashi | Queen Tsering Trashi | 18th century | Person | |

| rgyal tshab rje | Gyeltsapjé | 1364-1432 | Person | ||

| rgyal rabs gsal ba’i me long | Gyelrap Selwé Melong | The Clear Mirror: A Royal History | Tibetan text title | ||

| rgyal rong khang tshan | Gyelrong Khangtsen | Gyelrong Regional House | Monastery subunit | ||

| rgyugs | gyuk | examination | Term | ||

| rgyud stod | Gyütö | Upper Tantric [College] | Monastery | ||

| rgyud smad | Gyümé | Lower Tantric [College] | Monastery | ||

| rgyud smad grwa tshang | Gyümé Dratsang | The Lower Tantric College | Monastery | ||

| rgyun ja | gyünja | daily tea or prayer | Term | ||

| sgo gnyer | gonyer | temple attendant | Term | ||

| sgo srung | gosung | door-keeper | Term | ||

| sgom chen | gomchen | meditator | Term | ||

| sgom sde nam kha’ rgyal mtshan | Gomdé Namkha Gyeltsen | 1532-1592 | Person | ||

| sgom sde pa | Gomdepa | 1532-1592 | Person | ||

| sgra ’dzin chu mig | Dradzin Chumik | Sound-Catcher (or Ear) Spring | Place | ||

| sgrub khang | drupkhang | meditation hut | Term | ||

| sgrub khang dge legs rgya mtsho | Drupkhang Gelek Gyatso | 1641-1713 | Person | ||

| sgrub khang pa | Drupkhangpa | 1641-1713 | Person | ||

| sgrub khang sprul sku | Drupkhang Trülku | Drupkhang incarnation | Person | ||

| sgrub khang bla brang | Drupkhang Labrang | Drupkhang Lama’s estate | Organization | ||

| sgrub khang bla ma | Drupkhang lama | Person | |||

| sgrub khang ri khrod | Drupkhang Ritrö | Drupkhang Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| sgrub grwa | drupdra | practice center | Term | ||

| sgrub thabs | druptap | ritual method of realization | Term | ||

| sgrub sde | drupdé | practice-center | Term | ||

| sgrub phug | druppuk | meditation cave | Term | ||

| sgrol chog | Drölchok | Tārā Ritual | Ritual | ||

| sgrol ma | Drölma | Tārā | Buddha | ||

| sgrol ma lha khang | Drölma Lhakhang | Tārā Chapel | Building | ||

| brgya | gya | hundred | Term | ||

| brgyad | gyé | eight | Term | ||

| Nga | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| ngag dbang byams pa | Ngawang Jampa | 1682-1762 | Person | ||

| ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho | Ngawang Lozang Gyatso | 1617-1682 | Person | ||

| ngag dbang sman rgyal | Ngawang Mengyal | 20th century | Person | ||

| ngul gyi par khang | ngülgyi parkhang | money printing press | Term | ||

| sngags | ngak | mantra | Term | ||

| sngags pa | ngakpa | tantric priest | Term | ||

| sngags pa grwa tshang | Ngakpa Dratsang | Tantric College | Monastery | ||

| Ca | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| gcig bu pa | chikbupa | recluse | Term | ||

| bca’ yig | chayik | constitution | Term | ||

| Cha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| chab rdzing gling kha | Chapdzing Lingkha | Pond Park | Place | ||

| chu mo yos | chumo yö | female-water-hare (year) | Date | ||

| chu bzang | chupzang | good waters | Term | ||

| chu bzang | Chupzang | Monastery | |||

| chu bzang dgon | Chupzang Gön | Chupzang Nunnery | Monastery | ||

| chu bzang ye shes rgya mtsho | Chupzang Yeshé Gyatso | 1789-1856 | Person | ||

| cho ga phyag len | choga chaklen | ritual | Term | ||

| chos kyi rdo rje | Chökyi Dorjé | b. 18th century? | Person | ||

| chos kyi seng ge | Chökyi Senggé | Person | |||

| chos skyong | chökyong | protector deity | Term | ||

| chos khang rtse ba dgon pa | Chökhang Tsewa Gönpa | Chökhang Tsewa Monastery | Monastery | ||

| chos ’khor dus chen | Chönkhor Düchen | Festival of the Turning of the Wheel of the Doctrine | Festival | ||

| chos gos | chögö | yellow ceremonial robe | Term | ||

| chos rgyal | Chögyel | Dharmarāja | Buddha | ||

| chos rgyal khri srong lde’u btsan | Chögyel Trisong Detsen | the Buddhist king (of Tibet) Trisong Detsen | 742-796 | Person | |

| chos rgyal srong btsan sgam po | Chögyel Songtsen Gampo | the Buddhist king (of Tibet) Songtsen Gampo | 617-650 | Person | |

| chos thog | chötok | ritual cycle | Term | ||

| chos sdings | Chöding | Monastery | |||

| chos sdings ri khrod | Chöding Ritrö | Chöding Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| chos me khang | chömé khang | butter-lamp offering house | Term | ||

| chos mtshams | chötsam | doctrine retreat | Term | ||

| chos gzhis | chözhi | estate lands | Term | ||

| chos rwa | chöra | Dharma enclosure or Dharma courtyard | Term | ||

| mchod mjal | chönjel | worship | Term | ||

| mchod rten dkar chung | Chöten Karchung | Little White Stūpa | Monument | ||

| ’chi med lha khang | Chimé Lhakhang | Chapel of Deathlessness | Building | ||

| Ja | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| ja bdun dang thug pa gnyis | ja dün dang tukpa nyi | seven teas and two soups | Term | ||

| jo khang | Jokhang | Monastery | |||

| jo ston bsod nams rgyal mtshan | Jotön Sönam Gyeltsen | 17th century | Person | ||

| jo bo | jowo | the Lord | Term | ||

| jo bo mi bskyod rdo rje | Jowo Mikyö Dorjé | Buddha | |||

| jo mo si si | Jomo Sisi | Place | |||

| ’jam dpal bla ri | Jampel Lari | Mañjuśrī Peak | Place | ||

| ’jam dpal dbyangs kyi bla ri | Jampelyangkyi Lari | the Soul-Mountain of Mañjuśrī | Place | ||

| ’jam dbyangs grags pa | Jamyang Drakpa | Person | |||

| ’jigs byed kyi me long | Jikjekyi Melong | Mirror of Vajrabhairava | Place | ||

| ’jigs byed lha bcu gsum | Jikjé Lha Chuksum | Thirteen-Deity Vajrabhairava | Buddha | ||

| ’jog po | Jokpo | Monastery | |||

| ’jog po ngag dbang bstan ’dzin | Jokpo Ngawang Tendzin | b. 1748 | Person | ||

| ’jog po bla brang | Jokpo Labrang | Jokpo Lama’s estate | Organization | ||

| ’jog po bla brang | Jokpo Labrang | Jokpo Lama’s residence | Organization | ||

| ’jog po ri khrod | Jokpo Ritrö | Jokpo Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| ’jog po rin po che | Jokpo Rinpoché | b. 1748 | Person | ||

| ’jog ri ngag dbang bstan ’dzin | Jokri Ngawang Tendzin | b. 1748 | Person | ||

| rje btsun nam mkha’ spyod sgrol rdor dbang mo | Jetsün Namkhachö Dröldor Wangmo | Jetsün (or Khachö) Dröldor Wangmo | Person | ||

| rje btsun bla ma ngag dbang rnam grol | Jetsün Lama Ngawang Namdröl | Person | |||

| rje gzigs pa lnga ldan | Jé Zikpa Ngaden | Five Visions of the Lord (Tsongkhapa) | Painting series | ||

| rje shes rab seng ge | Jé Sherap Senggé | 1383-1445 | Person | ||

| Nya | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| nyang bran | Nyangdren | Place | |||

| nyang bran rgyal chen | Nyangdren Gyelchen | Buddha | |||

| nyi ’od pho brang | Nyiwö Podrang | Palace of the Rays of the Sun | Room | ||

| nye ba’i gnas bzhi | nyewé né zhi | Four Principal Sites | Place | ||

| gnyer pa | nyerpa | manager | Term | ||

| gnyer tshang | nyertsang | manager’s room | Term | ||

| rnying | nying | old | Term | ||

| rnying ma | Nyingma | Organization | |||

| rnying ma sgrub grwa | Nyingma drupdra | Nyingma practice center | Term | ||

| rnying ma pa | Nyingmapa | Organization | |||

| rnying ma bla ma | Nyingma lama | Term | |||

| snying khrag | nyingdrak | heart’s-blood | Term | ||

| bsnyen pa | nyenpa | approximation retreat | Term | ||

| Ta | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| tā rā’i bla ri | Taré Lari | the Soul-Mountain of Tārā | Place | ||

| trak shad | Trakshé | Buddha | |||

| gter | ter | treasure | Term | ||

| gter bdag srong btsan | Terdak Songtsen | Treasure Lord Songtsen | Buddha | ||

| gter nas ston pa | terné tönpa | discovered as treasure | Term | ||

| rta mgrin | Tamdrin | Hayagrīva | Buddha | ||

| rta mgrin gsang sgrub | Tamdrin Sangdrup | Hayagrīva in his “Secret Accomplishment” form | Buddha | ||

| rta ma do nyag | Tama Donyak | Place | |||

| rta tshag ye shes bstan pa’i mgon po | Tatsak Yeshé Tenpé Gönpo | 1760-1810 | Person | ||

| rtag brtan | takten | permanent and stable | Term | ||

| rtags brtan | takten | stable sign | Term | ||

| rtags brten | Takten | Monastery | |||

| rtags brten ri khrod | Takten Ritrö | Takten Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| rtags bstan | takten | revealed sign | Term | ||

| rtags bstan | Takten | Monastery | |||

| rtags bstan sgrub phug | Takten Druppuk | Monastery | |||

| rtags bstan ri khrod | Takten Ritrö | Takten Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| rten khang | tenkhang | Term | |||

| mchod rten | chöten | stūpa | Monument | ||

| bstan ’gyur | tengyur | Collection of Translated Śāstras | Tibetan text title | ||

| bstan ’gyur lha khang | Tengyur lhakhang | Tengyur chapel | Building | ||

| bstan nor mkhar rdo | Tennor Khardo | b. 1957 | Person | ||

| bstan ma | Tenma | Class of deities | |||

| Tha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| thang ka | tangka | Term | |||

| thang stong rgyal po | Tangtong Gyelpo | 1361-1485 | Person | ||

| thu’u bkwan | Tuken | 1737-1802 | Person | ||

| theg chen gso sbyong | Tekchen Sojong | Mahāyāna Precepts | Term | ||

| phyag stong spyan stong | chaktong chentong | Thousand-Armed Thousand-Eyed Avalokiteśvara | Buddhist deity | ||

| thogs med rin po che | Tokmé Rinpoché | 20th century | Person | ||

| thod smyon bsam grub | Tönyön Samdrup | 12th century | Person | ||

| thon mi | Tönmi | 7th century | Person | ||

| Da | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| dā ma | dama | Term | |||

| dā ma la nyag | Damala Nyak | Place | |||

| da lai bla ma | Dalai Lama | Person | |||

| da lai bla ma sku phreng dgu pa | Dalai Lama Kutreng Gupa | the Ninth Dalai Lama | 1806-1815 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng brgyad pa ’jam dpal rgya mtsho | Dalai Lama Kutreng Gyepa Jampel Gyatso | the Eighth Dalai Lama Jampel Gyatso | 1758-1804 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng lnga pa | Dalai Lama Kutreng Ngapa | the Fifth Dalai Lama | 1617-1682 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng lnga pa ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho | Dalai Lama Kutreng Ngapa Ngawang Lozang Gyatso | the Fifth Dalai Lama Ngawang Lozang Gyatso | 1617-1682 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng bcu bzhi pa | Dalai Lama Kutreng Chuzhipa | the Fourteenth Dalai Lama | b. 1935 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng bcu gsum pa | Dalai Lama Kutreng Chuksumpa | the Thirteenth Dalai Lama | 1876-1933 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng bcu gsum pa thub bstan rgya mtsho | Dalai Lama Kutreng Chuksumpa Tupten Gyatso | the Thirteenth Dalai Lama Tupten Gyatso | 1876-1933 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng drug pa | Dalai Lama Kutreng Drukpa | the Sixth Dalai Lama | 1683-1706 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng bdun pa | Dalai Lama Kutreng Dünpa | the Seventh Dalai Lama | 1708-1757 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng bdun pa bskal bzang rgya mtsho | Dalai Lama Kutreng Dünpa Kelzang Gyatso | the Seventh Dalai Lama Kelzang Gyatso | 1708-1757 | Person | |

| da lai bla ma sku phreng gsum pa | Dalai Lama Kutreng Sumpa | the Third Dalai Lama | 1543-1588 | Person | |

| ḍākinī | dakini | ḍākinī | Term | ||

| dam chen chos rgyal | Damchen Chögyel | Dharmarāja | Buddha | ||

| dung dkar blo bzang ’phrin las | Dungkar Lozang Trinlé | 1927-1997 | Person | ||

| dung dkar tshig mdzod | Dungkar Tsikdzö | Dungkar Dictionary | Tibetan text title | ||

| dung dkar tshig mdzod chen mo | Dungkar Tsikdzö Chenmo | The Great Dungkar Dictionary | Tibetan text title | ||

| dung dkar rin po che | Dungkar Rinpoché | 1927-1997 | Person | ||

| dur khrod | durtrö | cemetery | Term | ||

| dus ’khor | Dükhor | Kālacakra | Buddha | ||

| de bi ko ṭi | Debi Koti | Debikoṭi | Place | ||

| de mo sku phreng brgyad pa ngag dbang blo bzang thub bstan ’jigs med rgya mtsho | Demo Kutreng Gyepa Ngawang Lozang Tupten Jikmé Gyatso | the eighth Demo incarnation Ngawang Lozang Tupten Jikmé Gyatso | 1778-1819 | Person | |

| dog bde | Dodé | Place | |||

| dog sde | Dokdé | Dodé | Place | ||

| dog sde lho smon | Dodé Lhomön | Place | |||

| dwags po grwa tshang | Dakpo Dratsang | Dakpo College | Monastery | ||

| drag phyogs kyi las | drakchokkyi lé | wrathful magical powers | Term | ||

| drang nges legs bshad snying po | Drangngé Lekshé Nyingpo | The Essence of Eloquence that Distinguishes between the Provisional and Definitive Meaning | Tibetan text title | ||

| drug pa tshe bzhi | Drukpa Tsezhi | Sixth-Month Fourth-Day | Festival | ||

| drung pa brtson ’grus rgyal mtshan | Drungpa Tsöndrü Gyeltsen | fl. 17th century | Person | ||

| drung pa rin po che | Drungpa Rinpoché | fl. 17th century | Person | ||

| gdan sa | densa | seats of learning | Term | ||

| gdan sa gsum | Densa Sum | the three great Geluk seats of learning | |||

| gdugs dkar | Dukar | Buddha | |||

| gdugs pa’i bla ri | Dukpé Lari | the Parasol Soul Mountain | Place | ||

| gdugs yur dgon | Dukyur Gön | Monastery | |||

| gdung rten | dungten | funerary stūpa | Term | ||

| bdag bskyed | dakkyé | self-generation | Term | ||

| bdag ’jug | danjuk | self-initiation | Term | ||

| bde chen pho brang | Dechen Podrang | Palace of Great Bliss | Room | ||

| bde mchog | Demchok | Cakrasaṃvara | Buddha | ||

| bde mchog gi pho brang | Demchokgi Podrang | Palace of Cakrasaṃvara | Place | ||

| bde mchog bla mchod | Demchok Lachö | Offering to the Master Based on the Deity Cakrasaṃvara | Ritual | ||

| bde mchog bla ri | Demchok Lari | Soul Mountain of Demchok | Place | ||

| mdo skal bzang | Do Kelzang | Sūtra of Good Fortune | Tibetan text title | ||

| ’du khang | dukhang | assembly hall | Term | ||

| ’dra sku | draku | simulacrum (type of statue) | Term | ||

| rdo sku | doku | stone image | Term | ||

| rdo cung cong zhi’i phug pa | Dochung Chongzhi Pukpa | Cavern of Dochung Chongzhi | Place | ||

| rdo rje ’jigs byed | Dorjé Jikjé | Vajrabhairava | Buddha | ||

| rdo rje rnal ’byor ma | Dorjé Neljorma | Vajrayoginī | Buddha | ||

| rdo rje btsun mo | Dorjé Tsünmo | Buddha | |||

| rdo rje g.yu sgron ma | Dorjé Yudrönma | Buddha | |||

| rdo rje shugs ldan | Dorjé Shukden | Buddha | |||

| rdo rje sems dpa’ | Dorjé Sempa | Vajrasattva | Buddha | ||

| rdo gter | Dodé | Place | |||

| rdo ring | Doring | Clan | |||

| sdig pa chen po | dikpa chenpo | great sin | Term | ||

| sde srid | desi | regent | Term | ||

| sde srid sangs rgyas rgya mtsho | Desi Sanggyé Gyatso | 1653-1705 | Person | ||

| Na | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| na chung rtse mo ri | Nachung Tsemo Ri | Place | |||

| na ro mkha’ spyod ma | Naro Kachöma | Buddha | |||

| na ro mkha’ spyod ma’i bdag ’jug | Naro Khachömé Danjuk | Self-initiation Ritual of Naro Khachöma | Ritual | ||

| nag chu | Nakchu | Place | |||

| nag chu zhabs brtan dgon pa | Nakchu Zhapten Gönpa | Monastery | |||

| nag ril chen po zhig | nakril chenpo zhik | a large dark shape | Term | ||

| nang rten gtso bo | nangten tsowo | main inner image(s) | Term | ||

| nam mkha’ rgyal mtshan | Namkha Gyeltsen | 1532-1592 | Person | ||

| nor bu gling kha | Norbu Lingkha | Place | |||

| gnas kyi bla ma | nekyi lama | head lama | Term | ||

| gnas sgo gdong | Negodong | Monastery | |||

| gnas sgo gdong ri khrod | Negodong Hermitage | Monastery | |||

| gnas bcu lha khang | Nechu Lhakhang | Temple of the Sixteen Arhats | Building | ||

| gnas chung | Nechung | Buddha | |||

| gnas brtan bcu drug | Neten Chudruk | Sixteen Arhats | Ritual | ||

| gnas brtan bcu drug | Neten Chudruk | Sixteen Arhats | Buddha | ||

| gnas brtan phyag mchod | Neten Chakchö | Offering of Homage to the (Sixteen) Arhats | Ritual | ||

| gnas brtan bla ri | Neten Lari | the Soul-Mountain of the Arhats | Place | ||

| gnas bdag | nedak | site deity | Term | ||

| gnas nang | Nenang | Monastery | |||

| gnas nang dgon pa | Nenang Gönpa | Nenang Nunnery | Monastery | ||

| gnas nang ri khrod | Nenang Ritrö | Nenang Hermitage | Monastery | ||

| gnas mo | Nemo | Place | |||

| gnas rtsa chen po | né tsa chenpo | a holy site | Term | ||

| gnas ri | neri | mountain-abode | Term | ||

| rnam grol lag bcangs | Namdröl Lakchang | Liberation in Our Hands | Tibetan text title | ||

| rnam rgyal | Namgyel | Monastery | |||