Panorama of Sera, taken from the roof of the Great Assembly Hall.

(View Larger Version – for high-speed connections)

Hint: If either movie does not load properly, try refreshing this page. IE may take longer to load than other browsers.

This portion of the Sera Project website introduces Sera as an imagined, physical space. The fact that Sera has a physical location and a material dimension does not preclude its also having been imagined. For scholars of the human sciences, it is the interplay (we would say the dialectic) between these two dimensions – the imaginary and material – that is most interesting. It is certainly one of the things that most fascinates me.

The first of the three essays that you will find in this section presents you with examples of how the space of Sera has been imagined and represented chiefly by ethno/cultural outsiders, chiefly Europeans and Americans. The second essay introduces you to indigenous views of the site and its surrounding landscape. Through the example of Sera, it attempts to come to some general conclusions about Tibetan views of sacred space. Sera’s architecture – the totality of its buildings, compounds, perimeter walls, and so forth – is a means of dividing and organizing the physical space of the monastery. And this partitioning/organizing process is an important form of creating meaning. This is the subject of the third essay. Taken as a whole, the three essays provide the context for understanding the Sera interactive map, one of the most exciting parts of the Sera Project website. The three essays can be read sequentially (recommended), or independently. At any point you can skip the essays, and go directly to the interactive map.

A view of Sera from the mountain north of the monastery.

When people turn their gaze to the physical space of Sera, they see different things. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that what they see they en-vision – they imagine – and represent in different ways. In this introduction to the space of Sera we will explore some of the ways in which the monastery has been envisioned by different people, non-Tibetans, at different times, using a variety of media: from text to panoramic virtual-reality models. We will be dealing with material from the 19th century up to the present day.

Common sense would seem to dictate that the physical layout of the monastery is a given – that what is there is there ... period. But you will see from what follows that this is not so. That what is there for one group of people is not there for others, even at the same point in time. This will become especially apparent when you compare the views of non-Tibetans (found mostly in this section) with the views of Tibetans (found under Tibetan Perspectives). Euro-American scholars have their own jargon for the fact that space is not a given. They express this by saying that it is a construct: a construction that historically, culturally and linguistically-situated human beings create using their imagination and the tools at their disposal. Tibetan Buddhist thinkers express a similar view when they say that abstract concepts like space1 exist only as human conventions (tanyedu), as the “mere imputations of words and conceptual thought” (ming dang tokpé taktsam). That space is a construct or a convention does not mean that it lacks power or efficacy, quite the contrary. It is precisely because it is a human construct that it has the capacity to affect human lives.

Constructions, however, do not emerge from nowhere – they are not created ex nihilo. Certain tools are required for constructing a notion of a particular site – sacred or otherwise. Some of the differences in the visions of Sera you will encounter are the result of the fact that their creators utilize different tools – different media – to depict the space of Sera. A depiction of the monastery in words is going to be different from one in a painting, which in turn will be different from one in a photograph. But differences in media – differences in the modes of representation – do not explain all of the dissimilarities in the constructions of the space of Sera. At work here are other factors, like language, history, politics, and the sheer idiosyncrasy of human personalities.

So the medium of construction may not be the only thing that explains the differences in the various visions of Sera that we will encounter, but it is an important part of understanding these differences. We will structure our discussion according to media, and we begin with the medium of words, or text. Consider these alternative ways of describing the space of Sera in words (or actually, in words and numbers).

A plaque commemorating the official re-opening of the monastery in the early 1980s.

The great yellow-cap monasteries of Sera and Däpung were visited by some of us ... As the abbot had been notified that we were coming, his staff were ready at the gates to receive us ... Sera, which receives its name from a “hedge of wild roses” which used to enclose it, is situated, like Däpung, at the foot of the mountains, and lies on the northern border of the Lhasa plain some 2 miles from the city… Passing through the gate, we found the monastery was quite a little town of well-built and neatly white-washed stone houses with regular streets and lanes, some of which recalled those of Malta.2

Founded in 1419 by Jam Chen Choje, Disciple of Tsongkhapa, Sera Monastery has an assembly hall, three colleges, and thirty kansas. The monastery, occupying an area of 114964 square metres, is known as one of the three major monasteries of the Gelukpa, or yellow, sect ... [and] was appointed as a State-level Unit of Protection of Historical Relics by the State Council of P.R.C. in 1982.

NW corner = N 29.69920, E 91.13130.

NE corner = N 29.69674, E 91.13527.

SE corner = N 29.69541, E 91.13525.

SW corner = N 29.69827, E 91.13087.

With allowances for errors in the phonetic rendering of Tibetan terms (Sera has khangtsens, not kansas!), none of these characterizations of the space of Sera are, strictly speaking, wrong. Indeed, all of them impart important information about the site of the monastery.

All of them, however, also evince the idiosyncratic concerns of their respective authors. Waddell’s 1905 book, from which the above passage was taken, was a travelogue written during the late-Victorian era for a British, upper-class audience. Waddell wishes to make it clear that he actually visited the monastery (that he was actually in the physical space), and that he was received in a manner befitting his social stature. Both of these facts serve to legitimate his work, giving it credence in the eyes of his readers. In a narrative consistent with the genre of the travelogue, he situates the monastery vis a vis the other sites he visited, and offers comparisons to other places with which his readers may be acquainted (Malta).

The plaque placed at the monastery’s entrance by Chinese officials a decade after its reopening has touristic, bureaucratic and political functions. It provides visitors with certain geo-spatial facts (e.g., the physical size of the monastery), while simultaneously proclaiming its formal, bureaucratic status as an officially designated historical site. In the process, one is meant to glean that Sera, as a “historical relic,” both belongs to, and is held in high esteem by, the People’s Republic of China.3

Finally, the site of Sera can be depicted in abstract – here, numerical – terms, which, among other things, provides normally “soft” humanistic researchers with the legitimizing facticity otherwise reserved for the “hard” sciences.

Of course, none of these examples are drawn from the writings of Tibetan. If you are interested in exploring some of the ways that Tibetans themselves have envisioned the site of Sera, go to Tibetan Perspectives.

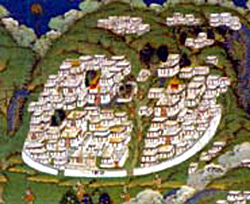

The space of Sera has been variously envisioned not only in and through narratives, plaques and GPS devices, but also pictorially. Consider these examples – three images of Sera, all created at roughly the same time in history.

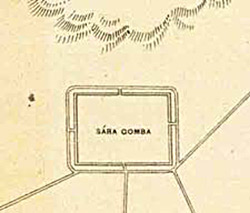

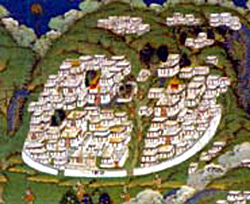

Detail from “A Plan of Lhasa,” published by the Survey of India in 1884. Portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, 8. |  Detail from a painting of Lhasa commissioned by a British official, c.1860. Portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, 20; the original is in the Wise Collection of the British Library. |  Detail of a Tibetan painting in the Musée des arts-asiatiques Guimet, Paris (Jean Schormans). Portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, inside cover. |

The contrast is stark. The first is from a document believed to be the first western- map of Lhasa, probably created by British colonial officials in India from the oral reports of Indian spies.4 The author is unknown. The second, while commissioned by a British official, was most likely painted by “a monk or a lay priest from the Nyingmapa school from Lahul.” 5 The last is from a traditional Tibetan painting (tangka) of the important religious sites in Lhasa.

In the first image, Sera is depicted as an empty rectangle sitting at the foot of stylized mountains. At equidistant points along its southern border, roads intersect its perimeter wall – or is this simply a frame for the words Sára Gomba (Sera Monastery)? The name of the monastery – in some strange fusion of phonetics and transliteration6 – substitutes for the detail that we find in the paintings.7 In the next image, the first of the two paintings, there is a commitment to greater detail on the part of the artist, but the image of Sera pales by comparison to that used to render, e.g., the Potala in the same painting, where every window is shown. The second of the two paintings, the traditional Tibetan image, renders the monastery in tremendous detail, for more on which see Tibetan Perspectives.

There are of course reasons for these differences in the depiction of Sera. The three images differ, first of all, because they are different visual genres – maps vs. paintings.8 But they also differ because their creators were differently motivated. They had different goals and reasons for representing Sera. The British mapmakers who were responsible for the first image were interested in gaining a general sense of the layout of Lhasa for strategic, military purposes. Maps such as this were part of their project of opening up Tibet to trade, a project that eventually led to the military invasion of Tibet, the so-called Younghusband “Expedition” of 1903-04. By depicting Sera in their map at all, they were acknowledging the existence of a large monastery to the north of the capital. However, it is the roads that appear to be of much greater interest to the British. Rather than simply reflecting a lack of information about the monastery, the fact that the site of the monastery is blank may be an indication that Sera was not perceived to be a significant factor in military planning, or, less likely.

A detail of “A Sketch Map of Lhasa” by L. Augustine Waddell, first published in 1905. A portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, 24.

When L. Augustine Waddell – part of the Younghusband military expedition – drew his own map half a century later, we find a bit more detail. For example, Waddell seems to be aware of at least one hermitage above Sera; and from his own visit to the monastery,9 he knew that Sera was bisected by a central street, a feature that is clearly visible on his map.

A great deal has happened to Sera since 1903. In the end, neither Tibet nor Sera were conquered by the British. But today there is a new onslaught of westerners into the monastery – perhaps more benign, perhaps not. Of course, I am referring to tourism.

A tourist map of Sera found in Mapping the Tibetan World (Reno, NV: Kotan Publishing, 2000, 84), by permission of the publisher.

Produced a century after the British maps, the concern of the tourist map is practical. Despite minor inaccuracies, it gives its intended audience useful information about getting to Sera from Lhasa (the minibus stop); it shows one where the ticket booth is situated, and it decides for its viewer the most important tourist landmarks (the large temples), even suggesting the route that one should follow (the culturally appropriate, Buddhist, counterclockwise direction). Maps are truly windows into their respective age.

The second of our original images – the Lahuli painting commissioned by a British official – also contributed to the general British project of assessing Lhasa and its environs, and while a military/strategic purpose is almost certain, this does not seem to have been its only – and maybe not even its chief – objective. As the number “74” next to the monastery suggests, the logic of “scientific” inquiry is at work here. It may be the case that the chief purpose of the painting was archival – that it was an attempt to identify and to catalogue the significant monuments of the capital. The detail – one large building surrounded by many smaller ones, all enclosed within a perimeter wall with three front gates – suggests that the artist was minimally familiar with the monastery. The choice to forego greater (or more accurate) detailing of features may be ascribed to a variety of factors, including the mandate given to the artist by the patron. Whatever the reason, Sera is not a prominent part of this painting, nor is the monastery considered sufficiently important to merit rendering it in a great deal of detail.

By comparison, in the last painting – the traditional tangka of Lhasa – Sera is very prominent. Even without allowing for corrections due to depth of field (the fact that images that are father away should – and do in this painting – appear smaller), Sera is (after the Potala and the Jokhang) the third largest compound in the painting. The level of detail affords the artist the opportunity to portray buildings three-dimensionally. The large temples, debate courtyards, the central “Sand Street,” monks’ living quarters, are all visible, down to a level of doorways and windows. Of course it is impossible to know precisely what the motivations or goals of the artist may have been, but it is likely that they were in part religious – that the painting was an homage to the great religious institutions of a great religious city. Just as artists take great care to correctly render the features and bodily proportions of deities, so too, in this painting, there is a concern for properly rendering the details of the sacred space of Sera. Hence, one might say that detail is almost a religious imperative, and not a matter of choice.

And now we turn to our last three images of the site of Sera. The first of these – an old, black and white photograph of Sera – was taken sometime before 1959.10 The second is a digital photograph of Sera taken by a member of the Sera Project research team in 2002. The third is a low-resolution version of a digital image of Sera taken on February 1, 2002 from the QuickBird satellite hovering above the earth.

Sera as seen from its from the east. |  Sera as seen from the mountain directly north of the monastery. |  Sera as seen from space. Copyright Digital Globe. |

All of the images are attempts at photographically representing the geoarchitectural space of Sera in its entirety. At least one of the images is in color, which is important because color allows one to distinguish features that would otherwise not stand out.11 There are also differences in the perspective, which shifts from lateral to vertical-lateral to vertical. This move toward greater verticality is the result of a new imperative to create a distinctively modern/scientific image of Sera: a geo-referenced, digital map. This, in turn, is essential to creating a Geographical Information Systems (GIS) model of a physical site like Sera. In a model of this kind, features on the map are coded. They are given meaning, if you will (as apartment houses, temples, and so forth).12 You will find a simplified version of such a meaning-laden map on this website. Of course, what is lost in this process of achieving greater verticality with respect to the object being represented is depth-of-field: the image appears flat. There exists, however, software for adding a third-dimension to such models (both in the landscape and in the buildings), and in future iterations of our work we hope to be able to do this.

Photography – of which all three of these images can be considered examples – may seem commonplace to us today, but it has radically changed the study of other cultures in the last century. The British “cultural officer” who accompanied the Younghusband expedition to Tibet in 1903, L. Augustine Waddell, was among the first westerners to take photographs of the sites of Lhasa – one of the first to render sacred space in this new medium. In the Preface to his famous travelogue, Lhasa and Its Mysteries (1905), he revels in the transparency of this new medium, a medium that permits him (and his readers/viewers), he implies, direct access to the truth of things. He believes that his photographs are “direct from Nature,” and that “the colour process” makes his photos “vivid and truthful pictures of the marvellous colouring of the originals.” 13 Waddell is telling us that cameras do not lie, and they don’t tell partial truths. Today, we are a bit less sanguine about the transparency of photography as a medium.14 Like all human products, photographs are seen to be laden with the presuppositions, concerns and purposes of their creators. The same is true of film. And by implication – because it is a medium that combines text, still photography, film, and their byproducts (like interactive virtual-reality models) – the same is true of multimedia digital projects like the present one.

Sera Monastery from the rear.

(View Larger Version – for high-speed connections)

Hint: If either movie does not load properly, try refreshing this page. IE may take longer to load than other browsers.

New technologies usually bring with them new hopes, but they may also bring unwanted consequences. As with Waddell’s expectations regarding photography a century ago, in the present digital age too there is a certain hope that new digital technologies will allow us to achieve a certain truth, and even a completeness of vision, that has heretofore been impossible to achieve. While it is true that digital imaging, and its dissemination through new delivery systems like the WWW, will undoubtedly revolutionize both research and pedagogy, there is also a tendency to overestimate the power of these new technologies.

Let me give you one example of this. Some folks believe (at least implicitly) that a geographical model of a site can, in principal, yield all of the information you could ever want to know about a place – that every bit of data could be referenced to a place on a map. I call this view spatial reductionism. It is a view that privileges space as a variable of analysis: all you need is… well, space. Here, points in space become the fundamental anchors or ground onto which all other information can be unambiguously mapped. There are many reasons for thinking that this view is naïve.15 I will not dwell on these because I am here interested in making another, broader point. Implicit in the spatial reductionistic view is what some contemporary philosophers call the “impulse to totalize.” Totalization is the tendency to think that completeness of vision is achievable, that we can perfectly capture everything that is worth knowing in its totality. Every new form of technology brings with it a new form of this tendency to totalize, and part of the task of digitally-committed scholars in the humanities today (the Tibetan wife of a close colleague calls us lokgyi mi – “electric people”) is to check, or at least to be aware of, this impulse to totalization. Nothing, not even computers, will ever allow us to achieve completeness, a God’s-eye view, and neither will any single variable of analysis – space, time (history) or anything else. And in the process of expanding our ever-partial knowledge, multiple perspectives – using different variables (from different disciplines), without privileging any of them – will always be the way to go.

Having said all this, I admit that the tendency to check this impulse to totalize is easier said than done. I find myself, for example, continuously reveling in the possibilities afforded by new digital technologies, and I confess to being insufficiently committed to realizing the partiality of vision that they afford. (The interactive map of Sera that you will see on this portion of the Sera Project website I find particularly astounding and promising, for example.) But being the child of a postmodern age, I realize that in time our day will come; that our work – the work of the “electric people” – will become the fodder for someone else’s critical inquiries; that our own presuppositions will be laid bare, and that new discourses will find nourishment and flourish in the ashes of this one. How or when this will come about is difficult to say, and so while we wait, I invite you to join me in feeling some of this excitement.

Since so much of the discussion of the physical space of Sera on this website presumes western, academic concerns and presuppositions, it might be interesting to ask how Tibetans view this same space. How do Tibetans conceive of the space that Sera occupies? How do they describe Sera’s whereabouts? How do they situate the monastery vis-à-vis other sites and the surrounding landscape? How do they envision the physical space around the monastery? What makes the land distinctive in their eyes? It will probably not come as a great surprise that Tibetans consider the site of Sera to be sacred (nechok dampa). But what does it mean for a site to be sacred? These are the types of questions we will explore here.

In some instances, the Tibetan views of space in general – and of the space of the monastery in particular – will seem familiar. In others, they will seem ... well, distant and remote. In the process of exploring these similarities and differences, our own conceptions of space and place may come to appear a bit less obvious, and a bit more idiosyncratic. This, I take it, is a good thing. It is part of the goal of, and reason for, studying other cultures, other places, and other people’s conceptions of sacred space.

What data shall we use to begin our investigation? We could look at a Tibetan map of Sera,16 or we could begin by simply asking Tibetans about Sera, or we could turn to texts, and see what Tibetans have to say about the site of the monastery in their writings. We will do all of these things in due course. But I propose that we begin to get a general sense of the way Tibetans en-vision the monastery not through words but through pictures. How is Sera as a physical site depicted in Tibetan art? Consider this fine example, of a 19th century Tibetan painting of the famous sites in and around the environs of Lhasa.

Painting in the George Crofts Collection, Ontario Museum, Toronto. Photo in Marilyn M. Rhie and Robert A.F. Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1991, 374-375); by permission of the photographer, John Bigelow Taylor

Sera is depicted above and slightly to the right of the central image, the Dalai Lama’s Potala Palace that towers above the city of Lhasa. Even if the map is not to scale, the relative position of Sera is approximately correct, since Sera lies north and slightly east of the Potala. The first thing to note – something that perhaps may go unnoticed because it is so obvious – is that Sera is part of the Lhasa landscape. In fact, Sera is the closest to Lhasa of the three large Gelukpa monasteries – the Three Seats of Learning (Densa sum).

When we look closer, we see that Sera is portrayed as a compound – a group of structures at least partially enclosed by a perimeter wall. (This, as we shall see, is also an important fact to notice, since in the section on Architecture I will claim that “enclosure” as a principal is central to Tibetan conceptualization of large monasteries.) On the front perimeter wall there are three gates. Above the monastery, in the mountains, are other, small structures. These are the famous hermitages (ritrö) that lie in the Sera foothills, one of which, Sera Chöding, is extremely important to the history of the monastery, as we shall see. The monastery appears to be divided into two halves by a north-south running crevice (painted brown in this painting). It has boulders in the middle of it, giving it the appearance of a streambed. This is the famous Sera Jezhung or “Sand Street.” As Geshe Rabten informs us in his biography, after heavy rains, the Jezhung would in fact serve as a runoff for water that came down from the mountains.17

Detail of the painting on left.

Finally, we see that amid the smaller, white structures, there are four large buildings partially painted in red to distinguish them from the rest. These are the four great temples of Sera – the Great Assembly Hall (to the right of the Jezhung) and the assembly halls of the Jé, Mé, and Ngakpa Colleges (to the left). The fact that these temples are prominent in the painting is also significant. It tells us something about the role they are perceived to have in the life of the monastery. What is less noticeable (because of size) is the fact that each of the smaller, white buildings are themselves compounds – of monks’ quarters and smaller temples that belonged to the residential houses (khangtsen) of the various colleges. All of these various features are found in an even more exquisite painting of Lhasa that has already been mentioned in the first section of this essay, En-visioning the Space of Sera.

The old eastern gate, no longer in use.

This painting varies in minor ways from the previous one. First of all, a greater number of buildings are shown, but this may represent nothing more than a greater stamina for detail on the part of the artist. The painting is also more true to the actual orientation of the buildings, in so far as they face SSW (as they do in the actual monastery). It also depicts the various debate courtyards, even if their position in the monastery is not entirely correct. The fact that the artist chose to depict the debate courtyards at all reveals the extent to which the monastery was associated with the activity of education, and the extent to which education was perceived in terms of one of its principal pedagogical modes – debate.

The second painting of Sera only shows two front entryways into the monastery, as opposed to the traditional three. The perimeter wall, and the “gates” or entryways of the monastery are important enough that legends have developed around them.18 Today, the main gate or entryway is located in the same place as the original entryway that we see in these paintings – at the bottom of the Sand Street – but it has been rebuilt.

Neither of the two minor gates to the east and west exist today. However, the old eastern gate does survive (inside the new perimeter wall), although it is in poor condition.

A new perimeter wall has been built to replace the ancient perimeter wall of the monastery. On the importance of perimeter walls within the monastery, see the section on Architecture.

The main gate of the monastery, taken during a festival day at Sera. |  Detail of thangka in the Musée des arts-asiatiques Guimet, Paris (Jean Schormans). Portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, inside cover. |

It is the mid-1950s, and you are standing in the center of downtown Lhasa. If you ask a group of Tibetans where Sera is located, they would most likely tell you that it is due north (byang phyogs la yod pa red). If you were to ask, “How far north?” they would probably tell you that it is an hour’s walk away. This is not a trivial observation, for it tells us something about the way that Tibetans view space and distance. Like us, Tibetans use the cardinal and intermediate directions (N, S, E, W, NE, etc.) to designate bearing. When it comes to designating the distance between two sites, however, they tend to opt for translating distance into time – the time that it takes to traverse the distance.19 In the mid 1950s, of course, there were few modes of transportation available. Most people simply walked. Thus, a given distance was conceived of in terms of the time that it took to walk it. (Today, a Tibetan in downtown Lhasa would probably tell you that by bus it takes about twenty minutes to get to Sera, and that by taxi it takes about ten.)

Not only is distance often expressed in terms of time, but on occasion time is also expressed in terms of distance. For example, in the evening debate prayer-assembly at the Jé College of Sera, there was a tradition of reciting the Heart Sutra – a famous scripture on emptiness – using a very slow tempo. This was done so as to give monks time to contemplate the meaning of the words they were reciting. As a result, the recitation took a great deal of time, or, as monks were fond of putting it, “it took as much time as it took to walk to Lhasa.”

Pilgrims make lungta (printed prayer) offerings on Space Soaring (Namkha Ding) Mountain during a pilgrimage festival day. Thus, the site of Sera is sometimes designated with reference to the mountains that surround it.

Direction and walking-time are typical ways to designate Sera’s location. There are others as well. Mountains are ubiquitous reference points in most of the Tibetan cultural world. Tibet is a mountainous land, and Lhasa is surrounded by mountains. One of the ways of identifying a particular site has always been with reference to specific mountains. In the case of Sera, some Tibetan historians identify the monastery as lying between specific mountains. Hence, Geshé Yeshé Wangchuk states that Sera “lies between the corner of Elephant Mountain [to the east], and Space Soaring Mountain [to the west].” 20

Tibetans also often conceive of a given space in terms of the natural phenomena that exist within it: the flora and fauna that inhabit or flourish in a given place. Sera too has been seen in terms of the attributes of its natural landscape. According to some Tibetan historians, the word Sera is an abbreviated form of sewé ra – literally, “wild-rose tip.”21 Hence, Sera Monastery (Sera Gön) was built, it would seem, on a site at one time known for its wild-rose bushes.22 It also appears that the site was known by this name even before the founding of the monastery. The hermitage that was Tsongkhapa’s home on and off for many years, located in the foothills just above what is today Sera was called Sera Chöding even before the founding of the institution of Sera.23 Unlike the other two large Geluk monasteries – Ganden and Drepung – whose names derive from Buddhist cosmology,24 the founders of Sera Monastery seem to have simply adopted the traditional Tibetan name of the site, one that derives from the attributes of the natural landscape.

The hermitage of Sera Chöding, above Sera, where Tsongkhapa taught and wrote for many years.

All of these forms of description we call “physical.” They involve conventions understood by almost anyone, and variables and reference points that are public and visible to anyone (the direction of the sun, mountains, plants, etc.).

Apart from these conceptions of place that derive from nature, landscape and the physical world, there are more metaphysical conceptions of Sera and its environs. For example, a contemporary Tibetan historian, and former Sera monk, Dungkar Lozang Trinlé writes:

This seat of learning [Sera] is believed to be one of the sites in the environs of the city of Lhasa where self-arisen [i.e., miraculous] mountains and rocks with eight auspicious signs have manifested. A protuberance on the middle mountain directly in back of [the monastery] has a shape similar to a victory banner. To the right of that mountain range there is something that looks like a clockwise-turning white conch shell. To the right, on the mountain in back of the Chubzang Hermitage, there is something that looks like a parasol. To the left, in the direction of the Neuchung Mountains, there is a rock face that looks like golden fish face-to-face.25

A self-arisen image (rang jung/jön) is usually a miraculously produced bas-relief of a deity or historical personage that emerges (super)naturally on a rock face, e.g., on a boulder.

Self-arisen images of the deity Tārā on a boulder behind Sera.

The images are self-arisen because they are not created or produced by human agents, but by the power or blessing of the deities, or “by the blessing of the truth of the nature of reality” itself.26 The idea that Dungkar Rinpoché is expressing, though, is slightly different, given that entire features of the mountains are being characterized as self-arisen images – not of deities but of the eight auspicious symbols. The point is that the sacrality of the site manifests in and through the physical landscape itself, molding the mountains so that they become signs of the site’s auspiciousness. Thus, the land around Sera is a land where the natural and supernatural merge, where sacredness is not inscribed in, but rather exscribed out of nature. The supernatural emerges out of the natural landscape, and these self-emergent signs acts as ciphers from which the sacredness of the space can be inferred. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that at play here is a notion of nature and the natural that is broader than our own.

Of course, Sera as a site is not unique in this regard. When the 18th century polymath Situ Panchen describes the area surrounding his monastery, he says:

This is a site that has collected a great expanse of goodness. The mountains to the right are like haughty turquoise dragons. The mountains to the left are like lions that roam the sky. The mountains in back are like crystal stupas, and in the front, like genuflecting elephants.27

For Situ Panchen too the sacrality or “natural goodness” of the site manifests in the natural landscape: in the fact that the mountains have distinct forms – principally, the forms of powerful and auspicious animals. When Jamgön Kongtrül, Situ Panchen’s spiritual descendent, a century later speaks of the site of his monastery (adjacent to Situ’s), he says that it appears in three ways to three different types of people. (1) To ordinary people it appears simply as a beautiful site (having few stones, thorns, free of wild animals, moderate in climate, with beautiful trees, flowers, mountains and streams, etc.). (2) To practitioners, it appears as a place perfectly suited to meditation, to the point where even “the mountain behind resembles a meditator; the lower meadow, crossed legs.” (3) To exalted or accomplished individuals, it appears as the abode of deities, as their celestial palaces.28

As Toni Huber states:

Mountains have, without a doubt, been the most venerated and culturally significant feature of the Tibetan landscape throughout space and time. Tibetans have considered various mountains to possess a special status or to be powerful or sacred in different ways for the entire period of their recorded history.29

In Huber’s own research on the Pure Crystal Mountain of Tsari, he notes that “written and oral accounts of the site image the regional geography as a gigantic ritual sceptre or dorje laid on its site,” with the mountain itself as a great, crystal stupa.30

This tradition of ascribing Buddhist meaning to the landscape goes back to very early times, perhaps even to the introduction of Buddhism into the country in the seventh century. Consider the way that Tibet is depicted in this beautiful poem ascribed to the first Buddhist king, Songtsen Gampo:

Mountains possessing good qualities were also there.

Tsagongin Tsari, Self-arisen Demchog,

And precious stones and waters31 were also there.

On the snows of Kailash there lived the 500 arhants,

And rivers of ambrosia existed in those mountains.

In Lake Mapang, a bodhisattva serpent-king dwelt,

And rivers possessing good qualities were also there ...

In the Namtso chugmo (lake) there were bodhisattvas,

And on Tanghla rock there were 500 arhants.

A bodhisattva serpent-king (dwelt) on the island of Lake Pub,

And there were multitudes of arhants on the snows of (mount) Ka’u.

Rito Satsang Snow Mountain was encircled by Nyen (spirits),

And their speech resembled the beautiful cadence of Sanskrit.32

When the whole of Tibet is envisioned as sacred, it is hardly surprising that the site of one of its great institutions, Sera, should also be so conceived. How else can one explain the success of the institution that thrived there? Great things don’t usually happen in bad places. The sacrality, auspiciousness, and power of the place thus serve as the metaphysical ground for the events that would unfold there – for example, the founding and flourishing of a great monastery.33

Trashi Chöling, one of the hermitages in the Sera foothills used by Tsongkhapa.

A good or auspicious physical site, however, is not enough to explain human or institutional flourishing. To put it the way a philosopher would, the sacredness of the physical space is at most a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for the success of institutions. Many causes and conditions (gyu kyen) actually go into making a space sacred. Chief among these is the fact that the space has been blessed (jingyi lappa).

How does a place come to be blessed? First and foremost, a place is blessed when holy beings (kyebu dampa) make it their home. These holy beings can be human or nonhuman. As H.H. the Dalai Lamastates:

The fact that many holy beings, spiritually advanced practitioners, stay and practice in a certain place makes the atmosphere or environment of that place change. The place gets some imprint from that person. Then, when another person who does not have much experience or spiritual development comes and remains in that place and practices, he or she can obtain certain special kinds of experience ... According to the Tantric teachings, at important places there are non-human beings, like dakinis, who have bodies that are much more subtle than those of humans. When great spiritual practitioners stay in a certain place and perform meditation and rituals there, that place becomes familiar to dakas and dakinis so that they may inhabit the place and travel around it ... This could also act as a factor influencing whether or not a place is considered special.34

The envoys of the Ming Emperor invite Tsongkhapa to China at Sera Chöding; from a mural in Kongpo Regional House (Kongpo Khangtsen).

Even before its founding, as we have seen, hermitages were ubiquitous in the Sera foothills. Several of these hermitages were places where Tsongkhapa had lived – where meditated, taught, where certain important historical events occurred, and where he had composed some of his most important works.

As Dungkar Rinpoché states:

On the mountain behind [Sera] the places where the great lord Tsongkhapa lived in retreat for long periods of time – places like Chöding, Seratse, Rakatrag, etc., with their meditation caves, practice huts and miraculous springs – can still be seen today. This is also the place where Khedrupjemet [his teacher], the lord Tsongkhapa, for the first time, and it is the place where [Tsongkhapa] composed his Great Commentary on the Root Text on the Middle Way. Sera Chöding is also the place where Tsongkhapareceived the envoys of the Tà ming Yung lo emperor, in the sixth year of his reign, in the earth-rat year (1408). These envoys had been sent to invite [Tsongkhapa] as chief chaplain to the court in Beijing\... It was also at Sera Chöding that [Tsongkhapa] charged Jamchen Chöje [with the founding of Sera]; it is where Jetsun Sherab Senge was made a teacher, and therefore where, symbolically, the glorious Lower Tantric College was founded.35

Tsongkhapa died in the same year that Sera was founded, and so he never saw even the first buildings of the monastery completed. But Sera monks believe that Tsongkhapa nonetheless had strong connections to the site of Sera, and this is because he prophesied its founding.36 Tsongkhapa composed his famous commentary on Nāgārjuna’s Root Verses on the Middle Way, entitled The Ocean of Reasoning (Rikpé Gyatso), in the hermitage of Sera Chöding around the year 1409.

A mural in Lhopa Regional House (Lhopa Khangtsen) showing Tsongkhapa teaching at Sera Chöding.

In the midst of writing this work, one of the folios of the text flew into the air in a gust of wind. It began to emit ཨ (“a”) letters (the symbol of the perfection of wisdom) in the color of molten gold.37 Some of the letters dissolved into a stone at the base of the hill and permanently imprinted themselves on it. Witnessing this, Tsongkhapa prophesied that this would be the future site of a great center of Buddhist learning, an institution of particular importance for the study and practice of the madhyamaka doctrine of emptiness. A decade later, Jamchen Chöjé Shakya Yeshé (1354-1435) founded Sera at this very site. Nor is Tsongkhapa the only holy being who is believed to have left his mark on the landscape of Sera. A mound of earth on one of the paths at the monastery’s eastern border is considered to be “one of the stupas that the Buddhist king Ashoka built when he built 10 million stupas in a single day.” 38

One of the things that makes the site of Sera special, then, is the fact that it was blessed by holy beings like Ashoka and Tsongkhapa. The blessing of the site by holy beings and deities is something that continues to occur, even after the monastery has been founded, like a battery that continues to be recharged. Hence, there are many later tales of miraculous events that continue to take place in the foothills of Sera: statues from India are found in its caves, miraculous images of deities emerge on its boulders, magical springs with curative waters suddenly begin to flow, etc.39 All of these events certainly bless the site, but they are also continuing indications (and vindications) of the activities that are occurring within the monastery, legitimating the institution as a place where goodness can and does continue to flourish.

Besides having been blessed in terms of its natural landscape, and historically blessed by important holy persons, the site of Sera has been blessed ritually. Tibetan Buddhist custom requires that a site be made suitable (lesu rungpa) before it can be built upon. This is usually done through complex tantric rites that involve, among other things, asking the indigenous deity of the site – the Zhidak, or “owner of the place” – for permission to use the land. In the case of Sera, however, it was Tsongkhapa himself who got the cooperation of Zhidag Genyen (Layman Lord of the Place):

The protector Zhidag, who is propitiated in Bati Regional House (Bati khangtsen). This is from a tangka painting in that regional house in Sera-India.

When the Lord Lama, the Protector Manjushri [that is, Tsongkhapa] was living and turning the wheel of the doctrine at Sera Chöding, Zhidag Genyen became his conscientious servant, and took on the task of protecting the wheel of the doctrine. And the Lord Lama, from his side, gave him the oath [to continue to serve as protector of the site in perpetuity].40

Zhidag today serves as one of the protector deities of Sera, and continues to be propitiated in the monastery.

The fact that the land needs to be ritually appropriated before it is fit for human use is of course an aspect of the Tibetan vision of space that – even if not unique to this culture – is important to the understanding of indigenous Tibetan notions of place. Human society may have established a convention of land-ownership, but in a prior and more fundamental sense, the original owner of the land is not human at all. And for the land to be used successfully, the permission of this deity must be obtained.

All of this together constitutes what I am calling the metaphysical conception of the space of Sera – “meta-physical” in the literal sense of the word as “beyond the physical.” Beyond the legal, political, geographical and other conceptions of the site, there is also operative this metaphysical sense of place and space, much of which is beyond the ken of the senses of ordinary beings. To understand this dimension of sacred space, a variety of metaphysical concepts must be invoked: the karma of the beings who inhabit a place, the deities who live above it in the sky, on the ground, or below the ground, as well as the notion of an intangible energy called “blessing.” In the Tibetan worldview the metaphysics of space does not negate the physical, more tangible, dimensions, but it operates alongside the physical in a dimension that, even if less palpable, is just as real.

Our emphasis throughout this essay has been on the actual site of Sera and its environs. Before 1959, however, Sera was a much larger political and economic entity than it is today. The monastery, colleges, and even many regional houses, and lama residences, owned estates, pasture lands, and real estate (e.g., houses in Lhasa). Moreover, the monastery, colleges and, sometimes, individual lamas had proprietary rights over other, smaller monasteries called branch monasteries (yenlakgyi gönpa). When all of this is taken into account, there emerges a vision of Sera as a network of institutions that encompasses a space much larger than that contained within the perimeter walls of the monastery. Since these will be treated under other subheadings, however, we are content just to mention this fact in passing.

Anthropologists use the term etic to refer to descriptions that are external to the worldview being described – descriptions that will usually not be accepted, and sometimes not even recognized, by the indigenous people being studied. An etic view of sacred space – and most anthropological discourse is etic – stresses the agency of human subjects or institutions in the creation of meaning.41 Sacredness is considered a human construct, and the job of scholars becomes one of describing the process of its construction, both synchronically and diachronically. Much of Huber’s (1999) masterful study of a pilgrimage mountain is written from such a perspective:

a meaningful, albeit visionary, architecture of landscape is generated and imposed on the natural environment ... [and] ritual and other forms of representation ensure that this subtle and naturally embodied architecture is regularly redefined at néri [mountain pilgrimage] sites.42

Huber’s goal is to show “that the néri cult appeared in connection with concerted Tibetan élite attempts to convert their culture thoroughly to a Buddhist one ... The néri tradition should be regarded as a complex product of the syncretism stimulated by the agency of so-called universal religions.43 ”

By contrast to etic forms of discourse, anthropologists speak emic views. Emic discourse usually emerges from – and is recognizable to – the culture itself. In an etic analysis, the scholar is concerned with demonstrating how, for example, the imperatives of history (e.g., the desire to convert Tibet into a Buddhist country) lead to a certain Buddhist “reading” of the natural landscape (a mountain as a crystal stupa, a Buddhist image). From an etic perspective, history serves as an explanatory mechanism for elucidating human behaviors (the behavior of reading Buddhist meaning into the natural landscape). The emic perspective is precisely the reverse of this. Most indigenous theorists are concerned with explaining history (the flourishing of Buddhism, and more specifically the flourishing of certain Buddhist institutions in certain places).44 The historical fact that Tibet flourished as a Buddhist country, and that Sera flourished as a Buddhist monastery, is something that requires explanation. The sacredness of the space becomes the mechanism for explaining a historical fact (the flourishing of Sera as an institution). As mentioned before, the presupposition here is that good things don’t happen in bad places. Thus the logic goes something like this:

- Why did Sera flourish at this particular site?

- At least in part because the site is sacred.

- How do we know the site is sacred?

- Because of the extraordinary signs evident in its surrounding landscape.

But what mechanism is at work in creating these extraordinary attributes in Sera’s natural landscape? What precisely constitutes the sacredness of a site so that it comes to exhibit these unusual environmental features? This brings us to yet another series of metaphysical arguments that have to do with the concept of karma.

The principal argument has embedded within it a logic similar to what in the philosophy of religion is called “the argument from design.” There the claim is that nature exhibits an order that can only be explained by positing an intelligent creator (God). In the present context a similar form of reasoning is at work. In the indigenous Tibetan view, the order visible in the landscape of Tibet is seen as proof of the fact that there are extraordinary, sentient forces at work. Mountains that look like conches, parasols and lions don’t simply arise by accident. They must be explained in some way. Tibetan Buddhist philosophers explain the order evident in the natural landscape in metaphysical (even if not theistic) terms. The environmental features of a given place come about as the result of the karma of the beings that are (or will be) reborn in that place. When these features are auspicious – as they are in the case of Sera, Lhasa and Tibet generally – then the karma that has created (and is sustaining) them must be good or virtuous; it must be a form of “merit” (sönam). Incidentally, the fact that Tibet has these extraordinary physical attributes as part of its natural landscape means that Tibetans are in some sense special, in so far as they possess the karma to create this place of auspiciousness. Thus, the sacredness of the land reflects, and is ultimately derived from, the sacredness of its people and their actions. More simply, good deeds cause good places to come about, and when the good people who created those good deeds are reborn in those good places, the places serve as the environment in which more good deeds can be created.

The fact that more good deeds can be created – to sustain, as it were, the auspiciousness of the natural landscape – does not, however, mean that they necessarily will be created.45 There is, after all, free will. If more good deeds are not created – if the bank account of merit is exhausted and not replenished – then the goodness of the place will cease, and the auspicious signs of its goodness, even in the natural landscape, will disappear.46 There are degrees, and an implicit order, to the exhaustion of merit (sönam dzokpa). First good institutions cease. That causes good people to disappear, and this, in extreme cases, can even cause the physical landscape to change – from auspicious to inauspicious.47 The last things to go are the signs of auspiciousness as these are found in nature. And even these can actually disappear. This, in any case, is the emic view. But as long as such signs remain, Tibetans believe, there is hope, because it means that one’s merit has not been totally depleted, and that there remains a “ground” for the possibility of goodness. And so long as there exists the possibility of goodness, so long is there reason to hope that the results of goodness will once again emerge in their fullness.

Architecture can be envisioned in many ways. Some architectural studies, for example, focus on the materials and techniques of building construction.48 While it is my hope that the Sera Project will be able to make a contribution to studies of this kind in the future, this is not my chief concern here. In the present essay I propose to take a somewhat different approach to the study of Sera as an architectural space. My focus will be on what I call the semantics of space – on the way that space is made meaningful through architecture, and, conversely, on how meaning can be inferred from the architectural partitioning of space.

Lay people work to construct a temple in this mural in Kongpo Khangtsen.

Architecture divides space, and it provides a means for its organization. Space is given meaning through this partitioning process, and through the organization of those parts. Thus, architecture is a meaning-producing, or semiological, enterprise. Perimeter walls, the walls of buildings and of rooms, ceilings, and roofs – all of them divide up space, creating the sense of inside and outside. That space is something that can be partitioned, creating enclosed areas (walls and what is in between those walls), is reflected in one of the Tibetan words for space, barnang, which literally means “the appearance of between-ness.”

Each culture has its own unique way of breaking up space through architecture, of creating meaning through the logic of inside and outside. In this essay you will learn about the way that architecture gives meaning to the space of Sera. The outside space of the monastery is subdivided and ordered by buildings and perimeter walls, and by the rules that govern the relationships of these various structures. Within a building, space is further subdivided and organized by rooms. In the present phase of the Sera Project the emphasis has been on external architecture, and so you will not find much about the interior of buildings at this stage. In the next phase of the project (2003-2004), our focus will shift to the way in which interior architecture produces meaning. Nonetheless, at the end of this section, you will have access to another essay that I published several years ago that deals in part with the interior architecture of Sera.

A typical compound, Gyelrong Chikhang, as viewed from above.

Before we begin our discussion of architecture, we should mention something that already may be familiar to you from other portions of the Sera Project website. This background will help to contextualize the discussion that follows. Sera is divided into three colleges (grwa tsang): two philosophical colleges (Dratsang Jé and Dratsang Mé), and one ritual college (the Tantric College [ngakpa dratsang]). The philosophical colleges are further subdivided into regional houses (khangtsen). Before 1959, when monks came from different parts of Tibet to study at Sera, they would enter a specific regional house. The region of Tibet they came from determined (for the most part) their regional house affiliation. There were seventeen or eighteen regional houses in the Jé College, and sixteen regional houses in the Mé College. With this by way of background, we are ready to begin.

An entryway into a compound. Bati Regional House (Bati khangtsen).

Buildings at Sera can be classified according to their form:

- A compound is an enclosure: a single building, or group of adjoining buildings, with an interior courtyard. The buildings themselves act as the outside walls of the compound. Where buildings do not completely enclose a compound, there one finds a perimeter wall. Compounds are roughly quadrilaterals, accessible by one or more entryways. Entryways can be passageways through one of the buildings, or else they can be gates/doorways in the perimeter wall of the compound.

- A complex is a grouping of adjacent (though not necessarily adjoining) buildings that share some kind of association. They may have a courtyard, but have no perimeter wall. Complexes are therefore not enclosed, and this is principally what distinguishes them from compounds.

- Freestanding buildings are buildings with no specific association to nearby buildings, and with no perimeter wall.

A freestanding building, presently an individual monks’ living quarters, located at the NW corner of the monastery. |  Gungru Regional House (Gungru Khangtsen), as viewed from outside the compound. The temple building is visible on the right, and the entryway to the left. Most of the rest of the compound is surrounded by a perimeter wall. |

These distinctions are purely formal. They are part of a general architectural typology that are not specific to Sera, but all of these “types” are found at Sera. The most common architectural form at Sera, by far, is the compound.

Compounds at Sera are of three types:

- Main regional house (khangtsen) compounds. These are compounds that serve as the main administrative centers for the regional houses, the sub-units of the two philosophical colleges. Almost all of the regional house headquarters of Sera were built as compounds. Those that today are not enclosed (e.g., Trehor/Driu and Ngari) may have been so originally. In a regional house compound, the north wing contains the regional house temple, called tsom, whose main door always faces south. The regional house kitchen (khangtsengi rungkhang), usually painted yellow,49 is sometimes part of the northern (temple) wing, but it may also be located in another part of the regional house. Monks’ living quarters (drashak), usually two or three stories, comprise the other three wings of the compound. All of these surround a central, interior courtyard (gora nangma). In the courtyard of some of the larger regional houses one sometimes finds a regional house debate courtyard (chöra): a separate sub-courtyard with a debate throne (damtri) and its own perimeter wall that partitioned it off from the rest of the regional house courtyard. Smaller regional houses did not have the luxury of having a separate debate courtyard, and instead maintained a debate throne in the main courtyard itself, using the entire courtyard for special debates (damcha) as the need arose.

- Apartment (chikhang) compounds. In addition to the main regional house compounds, many regional houses also had separate apartment buildings. These were probably built later, as overflow housing, when the monks’ living quarters in the main regional house compound were no longer sufficient to house the regional house’s monks. Most, but not all, of the apartment houses were compounds. That is, they were built around central courtyards. Apartment compounds did not contain temples, large common kitchens or debate grounds. They were strictly living quarters for monks, sometimes three or even four stories on each wing, sometimes with a different number of floors on different sides. Most of the wings of an apartment building had balcony walkways facing the courtyard, with the entrance to the rooms along the walkway. But in some instances one of the wings of monks’ rooms might be an enclosed building with no balcony walkways. In this case, access to the rooms was through interior hallways.

- Lama residence (labrang) compounds. Some lamas, or recognized incarnations (trülku), were sufficiently wealthy, or had sufficiently high status (or both) that they owned their own compounds. Like the apartment compounds, these tended to be only residential quarters, with four wings of rooms around a central courtyard. The exception appears to be Tsomonling Labrang, which seems to have had its own temple.

Hamdong Regional House (Hamdong Khangtsen). The temple is on the left, the regional house kitchen on the right, and monks’ quarters in the center.

A debate throne, built under a balcony walkway, in the small Metsang Regional House (Metsang Khangtsen). |  The Ngari Apartment Compound (Ngari Chikhang). |

Balcony walkways along a wing of monks’ quarters in the huge Hamdong Chikhang (Hamdong Chikhang). |  The Ketsang Labrang Compound, three stories built around a central courtyard. |

The Great Assembly Hall of Sera, where all of the monks from all three colleges would gather for common rituals. |  The Mé College Assembly Hall. The canvas awning covering the portico contains auspicious symbols. |

The only complexes at Sera are the large temple complexes: the assembly halls (dukhang), of the three colleges, and the Great Assembly Hall (Tsokchen). A large temple complex contains a huge, multi-storied temple, and one or more separate kitchen buildings. The exception is the Tantric College, whose kitchen is found inside the temple (on the ground floor, SW corner).50 The three colleges also have large debate courtyards (chöra) as part of their complexes. (Since they are enclosed by perimeter walls, these debate courtyards are themselves compounds).

Assembly-hall temples have large stone-paved courtyards (dochel) in front of them. The temple always faces south (see below), and is built several feet off the ground, so that one has to climb stairs to get inside. These stone stairs lead to the temple portico (gochor). Temple porticos – both in large temples and even in the smaller regional house temples – are protected on their open, front (southern) side with a canvas or wool awning. Their walls are painted with exquisite and elaborate murals (depri) on a variety of themes. 51 Side doors (E and W) off the portico lead to stairs that access the upper stories of the temple. The main door (N) leads to the main meeting hall (tsokkhang). Side and rear chapels (lhakhang)52 are found all along the main meeting room. That main room receives its light from a clerestory, a square projection in the middle of the room that extends beyond the roofline and contains windows that open up into an ambulatory on the second story of the temple.

The temple, now administrative offices, of the exquisitely restored Tsomönling Labrang. |  Mé College kitchen, painted yellow, as are most kitchens in Sera. |

The second stories of assembly-hall temples contain a variety of rooms all built around an al fresco ambulatory that goes around the central, square clerestory. From the clerestory windows, one can look down into the interior of the main meeting hall below. Meeting rooms for administrators are found on this second floor, the largest of which is usually on the front (S) side, above the portico. It contains a row of south-facing windows that are visible from the outside. The second story also contains chapels (usually E and W), and living quarters. The multiple floors of the abbot’s suite, and the Dalai Lama’s suite are found in the rear (N) of the second story, and project multiple stories above it.

A word diagram, a mural on the Jé College temple portico. This diagram uses the syllables of the mantra Om mani padme hum |  Workmen paint the clerestory windows on the second floor of the Jé College Assembly Hall. |

The multi-story kitchens of assembly-hall temple complexes are always adjacent to the temple, and can be located to its east (as is the case with the Great Assembly Hall and the Mé College), or to the west (Jé College). Kitchens not only contain the hearth building/room, but also living quarters for cooks and other workers, storerooms and their own courtyards. The Jé College is unique in having two sets of kitchen buildings: one for special ritual events sponsored by the laity (painted white), and one for the daily use of monks (painted yellow).

The clerestory ambulatory on the second floor of the Tantric College temple, with the windows that look down into the main temple on the right. |  The Samlo Regional House (Samlo Khangtsen) Stupa, the older of the two stupas at Sera. |

A variety of freestanding buildings are also found at Sera. Before 1959, these were few in number: the printing house (parkhang), the stables (tara), the Samlo Stupa (Samlo Chörten), and possibly some storerooms and clay tablet repositories (tsatsakhang). Today, in addition to these, there are a variety of other freestanding buildings: a classroom building (dzindra tsoksa), several individual monks’ residences (khangpa), a museum (dremtönkhang), a restaurant (zakhang) with an infirmary (menkhang) above it, a tangka display building (from the top of which the giant painting of Maitreya is unfurled once a year during the Zhotön Festival), a new stupa, and a ticket booth (where foreign tourists must buy their admission’s tickets for entry into the monastery).

Of the major structures at Sera, there is one that we have not yet discussed in this section. It is the perimeter wall of the monastery. Enclosure walls are a ubiquitous feature of traditional Tibetan architecture, and they serve a variety of practical functions. For example, they serve to enforce real-property rights, and they function to provide security – e.g., protection from thieves.

But in Tibetan monasteries, perimeter walls also function in more symbolic ways. Clearly, they serve symbolically to separate the monastery from the outside world: the sacred from the profane. They also symbolically serve to include people (the monks who keep the discipline), and to exclude people (those who break their vows). Waddell describes what used to happen to monks when they broke one of the major monastic vows (for example, the vow against stealing):

... the accused is taken outside the temple and his feet are fastened by ropes, and two men, standing on his right and left, beat him to the number of about a thousand times, after which he is drawn by a rope outside the boundary wall (lchags ri) and there abandoned.53

A monk is expelled from the monastery (literally, from the “roles,” kyigüné) by physically and ritually taking him outside of the monastery – that is, outside the perimeter wall. The perimeter wall also allows monks and lay people to know in a very precise way when they are within the monastery, and when they are outside of it. Why is this important? During the rainy season, for example, monks take vows to remain “within the bounds of the monastery.” To leave the monastery – to go beyond the outer perimeter without undergoing the proper “release ritual” – is to break the rainy season retreat discipline. Additionally, although women could visit the monastery by day, before 1959 no woman was allowed to remain within the monastery – that is, within the perimeter walls – overnight.54 Thus, setting and maintaining boundaries or perimeters was important to keeping the monastic discipline, or Vinaya. Over and above the mundane reasons for enclosures, therefore, there were also religious reasons for conceiving of the monastery as a fixed and precisely determined enclosed space.

A portion of the monastery perimeter wall at the NW corner of the monastery. A small clay-tablet repository can be seen on the right. |  A view of Sera from above, where the internal subdivision of the monastery into compounds is evident. |

A regional house compound as seen from above.

Just as a perimeter wall was used to separate the monastery from the outside world, perimeter walls around the monastery’s various compounds served to divide the institution up internally. The Great Seats of Learning (Densa) were scholastic institutions, and scholastics revel in orderliness – everything in its place.55 Because of the sheer size of Sera, such orderliness was not only an ideological or aesthetic desideratum, it was also a practical imperative. Knowing what belonged to whom was necessary to maintaining the peace. Once the limits of Sera had been set, the monastery could not easily expand. Space being at a premium, one can imagine that monks would want to prevent other monks from encroaching on their turf. Thus, creating clear boundaries between the various compounds – the regional houses (khangtsen), their affiliated apartment buildings (chikhang), and the independent lama residences (labrang) – was probably something that evolved over time out of sheer necessity. It prevented squabbles over land. Having enclosed compounds was also a way of maintaining security and discipline. The main door to a compound that housed monks’ living quarters could be locked at night, ensuring not only that intruders could not get in, but also that monks (especially younger monks!) could not get out. A perimeter wall thus encloses almost every structure at Sera that contains monks’ living quarters.56

In Sera-India, an elder monk performs the rainy season release ritual to allow two of his students to exit the monastery. |  The Great Assembly Hall, and its open anterior courtyard. |

Southern view from Sera, with the Potala in the distance.

Practically the only major structures that are not enclosed by a perimeter wall at Sera are the large temple complexes – the assembly halls of the colleges, and the Great Assembly Hall. First, as the locus of power within the monastery, the colleges and the central Sera administration (before 1959, housed in the Great Assembly Hall) did not have to worry as much about protecting their land. Second, perimeter walls would have somewhat impeded lay worshipper’s access to the temples. Third, very few (and mostly elder) monks – abbots, administrators, and their staffs – lived in the assembly halls, and there was obviously less need to restrict their movements. Finally, and probably most important, perimeter walls around the main temples would have worked against the aesthetic of grandeur that the architects of these monumental structures were attempting to achieve.

The south-facing rooms atop the Jé College, where the abbot’s residence and the Dalai Lama’s guest rooms were located.

A detailed discussion of the interior layout of the various kinds of compounds is planned for the future. But there is one aspect of the interior layout of compounds that is worth mentioning here: the direction of temples. In the Tibetan spatial imaginary, the temples of Sera are its very heart. This is evident from paintings examined in the section on Tibetan Perspectives. Temples are the abodes of deities. They are the sites where monastic and other forms of ritual are enacted. Temples are the chief places visited by lay worshippers when they come to the monastery. When Tibetan historians write about Sera, they devote what may seem to us like a disproportionately large portion of their works discussing temples – their founding, history, and especially their contents. Temples were, and still are, important.

Now in almost every instance, the temples of Sera – both the large temples and those found in the regional houses, close to forty of them before 1959 – face almost exactly south. This cannot be explained simply in terms of the need to capture interior light in the temple meeting hall, or by the need to provide the temples with heat. On the one hand, temples usually have no windows in their main halls, and the south-facing door, situated on a portico behind an awning, provides little light, let alone heat. Light comes instead mostly from upper-floor clerestory (or skylights). There is no doubt that south is the preferred direction in Tibetan architecture,57 especially in the case when a monastery is built – as Sera is – in the foothills of a south-facing mountain. Generally speaking, it is the direction of most light, it is the direction with the best view, and in the case of Sera, it is the direction that faces Lhasa, and the Potala. As the preferred direction, it is fitting to orient temples – the holiest places in the monastery – southward. As the residence of deities, temples would be oriented south as an act of homage to the supernatural inhabitants of the temple abode. We must also remember that the upper stories of temples served as the residential quarters for monks, and not just any monks. Hierarchs (lamas, abbots, senior teachers) and senior administrators (of the monastery, colleges, or regional houses) lived on the upper floors of temples, and it was principally there that they worked. So perhaps it was also in deference to the senior monks of the monastery that temples were built facing south.

Obviously, a great deal more could be said about the architecture of Sera, and the logic at work there in partitioning and organizing space. For the time being, however, this will suffice. If you want to explore the principals of architecture and their relationship to Tibetan scholastic philosophy, you can go to one of my previously published essay entitled Tibetan Gothic, Panofsky’s Thesis in the Tibetan Cultural Milieu.

Skip guide and go straight to the interactive map.

A few words by way of orientation may help you to better make use of the interactive map you are about to see. Sera is located about two miles north of Lhasa at the foot of the mountains. The monastery occupies a one-third square kilometer area (about the size of a large university campus in the U.S.). It is divided into two approximately equal halves by a kind of boulevard called the “Sand Street” (Jezhung). It has a variety of buildings and structures – from small (nine square meter) clay-tablet repositories to the huge “regional house” (khangtsen) compounds. To gain a better sense of the different types of compounds and buildings at Sera, see the “Architecture” section of this essay.

Sera is both a physical site and a social institution. As an institution, it is arranged hierarchically, and this hierarchy expresses itself in a complex way in the organization of the physical space of the monastery.

The organizational hierarchy can be expressed schematically as follows:

Sera Monastery

- Jé College (Dratsang Jé)

- Seventeen or eighteen regional houses (khangtsen)

- Mé College (Dratsang Mé)

- Sixteen regional houses

- Ngakpa (Tantric) College (Ngakpa Dratsang)

This is fairly simple. The monastery is divided into three colleges, and the first two of these – the two philosophical colleges, Jé and Mé – are further subdivided into regional houses. The Tantric College has no regional houses.58

This straightforward organizational scheme does not, however, translate in a simple fashion into the spatial organization of the monastery. The different buildings affiliated with the different colleges are not found together in the same part of the monastery. Instead, they are scattered throughout the entire space of Sera. The same is true of the regional houses. Buildings belonging to one regional house can be found at opposite ends of the monastery. There are also a few buildings that have no affiliation to any of the colleges, and that thus belong only to Sera as a whole. A prime example is the Great Assembly Hall. This temple complex is, as it were, the common property of Sera in general.

One of the virtues of the interactive map is that it allows you to explore how the organization of the monastery translates into – how it is expressed in – the physical space. Thus, by “turning on” the College Affiliations, for example, you can see all of the buildings affiliated to each Sera’s three colleges, and those that have no affiliation to any of the colleges, but only to Sera in general.

In addition, there are various types of building-complexes, compounds, free-standing buildings and structures in the monastery, and you can gain a sense of how these are distributed within the monastery by turning on the Features button. For example, regional houses as organizational units contained two main types of structures: the regional house headquarters (that contained the regional house temple, administration, and some monks’ living quarters, see the “Architecture” section of this essay), and apartment buildings (that contained only residential quarters for monks). Each of these is coded a different color, and is clearly distinguishable, when the Features button is turned on. Thus, Features allows you see where all of the main regional house compounds are located, and also where large temple complexes, college debate courtyards, and many other types of buildings are found in the monastery.

You can also find a specific building or group of buildings by clicking on it/them under Specific Buildingslist. For example, you can see all of the specific buildings associated with a given regional house by clicking on that particular house. Or, if you want to find the Mé College temple complex, you could click on that, and it will be highlighted on the map.

In this way, the map allows you to see how the space is organized (a) in terms of organizational affiliation, (b) in terms of types of building, and (c) in terms of specific buildings or groupings of buildings.

Finally, clicking on a building or compound on the actual map gives you access to more detailed information about that unit, and provides you with a link to information about the organizational unit to which it belongs. This data window also gives you access to the photographic archive related to that building. Since our work to date has focused mostly on the exterior architecture of buildings, do not expect to see much of their interiors, at least not yet.

Go to the interactive map now.

The map that you are about to see is the result of many hours of work on the part of many people (see Collaborations and Credits). Buchung, of the Tibet Academy of Social Sciences (TASS), helped us create the necessary contacts in the monastery, and accompanied us on several data-gathering trips. Tsewang Rinchen, the head librarian at TASS, made available to us a detailed map of the monastery that was extremely helpful to us in our day-to-day fieldwork. Prof. David Germano of the University of Virginia made all of the THL media equipment in Lhasa available to us.

The data on which the map is based was collected during a month-long research trip to Tibet organized by José Cabezón in 2002. Cabezón and David Newman spent almost every day at Sera. Cabezón was chiefly responsible for identifying all of the major structures within the monastery, gathering data for what was to become the database portion of the map. Newman was chiefly responsible for taking high-resolution digital images and GPS readings at all of the sites. Two student assistants, Taline Goorjian and Alyson Prude, typed up the daily field notes from a digital voice recorder. The monks of Sera-Tibet were extremely helpful whenever we had questions or problems. In August, Cabezón continued to work at Sera-India, and here too many monks were extremely helpful in answering questions.