The Deer and Wheel, the symbol of the Buddha’s teaching, found atop each of the assembly halls of the colleges of Sera.

A college (dratsang) – literally, a “grouping of monks” – in Gelukpa parlance is a subunit of a large monastery. All of the large Gelukpa academies (densa) are subdivided into colleges. Every monk of a densa has an affiliation (khung) to a college, and this was an important part of his identity, defining him in unique ways – from the prayers he chanted, to the deity or deities he venerated, to the texts he studied. There existed a (usually) friendly rivalry between colleges within a given densa, and also across the densas. This was especially true of the philosophical colleges (see below). For example, the monks of the Jé (Dratsang Jé) and Mé (Dratsang Mé) Colleges of Sera were rivals, but so were the monks of Jé College and the monks of Loselling College (Dratsang Loselling) of Drepung Monastery. So long as this rivalry was kept within limits, this was seen as useful, and senior teachers encouraged it, albeit mostly in subtle ways. Monks who studied would try to outdo each other (in memorization, debate, and learning) so as to bring honor to their college, and this competitive spirit was seen as a positive thing. The same type of rivalry, by the way, existed between the regional houses (khangtsen) within a given college.

Colleges in the densa were of two types:

- philosophical college (tsennyi dratsang)

- ritual (kurim) colleges or tantric college (ngakpa dratsang)

The philosophical colleges were originally created as professorial chairs – that is, as the seats of individual teachers, where they could instruct monks in one or more of the classical subjects that constituted the scholastic curriculum of studies.1 When, shortly after the founding of the densa, the monastic populations of these institutions began to grow, and it was no longer feasible for the throne-holder (tripa) of the monastery to serve as instructor for all of the monks, they2 created various subunits called “colleges,” placing their senior students as the preceptor (loppön),3 that is, as the head teachers, of each of these colleges.4 This eased the burden on the throne-holder by shifting the instructional and spiritual responsibility for new students to his senior students. For new monks it probably provided a less impersonalized learning experience by giving them a more intimate connection to a teacher that had fewer responsibilities and fewer students, and who was therefore more accessible.

Young monks receiving instruction from one of the senior teachers of Tsangpa Regional House (Tsangpa Khangtsen), Sera-India.

What had earlier transpired at the level of the monastery eventually occurred at the level of the college. The colleges themselves grew in size, and the position of “instructor” became more of an administrative position, eventually called abbot (khenpo). The colleges were formally subdivided into smaller units called regional house, and these now became the new seats for senior teachers. Thus, in time, teachers at the regional house level came to replace the college master or preceptor as the locus of instruction.

Before 1959, each of the colleges had its own separate administration: a council consisting of the abbot (the supreme authority who wielded a great deal of power), the disciplinarian, the chant master, several college-level administrators, and “regional house teachers.”5 The administrative headquarters of each college was located atop its respective assembly hall (je dukhang), where the abbot also dwelt.

Young monks engage each other in an argument during an evening debate session at Sera-India.

The chief mission of the Geluk philosophical colleges was (and is) to train students in the philosophical classic (zhung chenmo) of Indian Buddhism as these had been interpreted by Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Geluk school, and by his chief disciples. The Geluk school in particular puts tremendous emphasis on the study of the Indian texts. There are many reasons for this. Here we shall cite just two. Tsongkhapa believed that the great tradition of Indian scholastic Buddhism represented the apex of Buddhist learning. To the extent that Tibetan Buddhism had departed from that tradition (and Tsongkhapa believed it indeed had) it was seen as having degenerated. Therefore, Tsongkhapa and his followers saw one of their chief tasks to be that of bringing Tibetan Buddhism back to its Indian roots.

More fundamentally, perhaps, the Gelukpa emphasis on philosophical studies has to do with the perceived relationship of these studies to practice (and especially to the practice of tantra (gyü)). Geluk generally believe that to practice tantra the student must have evolved certain spiritual qualities or mental traits: (a) a level of renunciation (ngenjung), a disgust with the pleasures and concerns of the world, (b) a proper motivation, as epitomized by the thought of enlightenment (jangchupkyi sem), the overwhelming wish to attain enlightenment for the sake of others, and (c) a correct understanding of reality, called right view (yangdakpé tawa). Although there were systems for developing these traits independently of prolonged formal philosophical study – for example, through the study and practice of the so-called stages of the path (lamrim) tradition6 – it was generally maintained that the most effective and profound way of engendering these qualities was through the study of the Indian classics. Having a conceptual understanding of Buddhism was seen as a necessary preamble to successful practice. Since the great texts of Indian Buddhism were seen as providing the most detailed blueprint of the theory and practice of the path, it was the texts of the Indian tradition that came to be considered the norm. A curriculum of studies was instituted in the Geluk academies shortly after their founding. Its raison-d’etre was to provide monks with a structured environment in which to engage in the intensive study of the Indian doctrinal/philosophical tradition.7 A monk’s successful completion of the curriculum culminated in the prestigious degree of geshé, and only students in the philosophical colleges were candidates for the four ranks of geshé degree.8 (Click here to read more about the geshé degree.) To achieve the highest rank of geshé, a monk had to spend twenty or more years in a rigorous program of study and prayer. Monks would progress steadily through thirteen different classes that covered five major subjects:

- Collected Topics (Düdra)

- Perfection of Wisdom (Parchin)

- The Theory of Emptiness, or Madhyamaka (Uma)

- Monastic Discipline (Dülwa)

- Metaphysics/Cosmology (Dzö)

Logic/epistemology (Tsema) was studied in a Special Winter Interterm (Jang Günchö) held at a separate monastery south of Lhasa. Monks of all of the densas attended this interterm. (Click here to read more about the curriculum)

Monks who studied, called “textualists” (pechawa), spent many hours every day in study and prayer. Study consisted principally of memorization (löndzin), (Click here to read more about memorization.) debate (tsöpa), (Click here to read more about debate.), and reading (pelok gyappa), although monks also received sporadic tuition or oral commentary on the texts (petri) from their teachers. The curriculum, as we have mentioned, was based on the great texts of Indian scholastic Buddhism, and on their Indian and Tibetan (Gelukpa) commentaries. In actual practice, however, most monks spent the majority of their time studying, and debating from, the college textbooks (yikcha).

Probably less than 25 percent of all monks in the philosophical colleges, however, were textualists. The remaining monks were mostly workers. Most monks, but especially textualists, spent a good part of their day in prayer assemblies, and prayer was seen as an essential part of the educational process. Prayer, or more generally the accumulation of merit, is believed to clear away obstacles to learning: physical obstacles (such as illness and financial hardships), as well as mental/psychological impediments (like the inability to memorize, to analyze arguments and to understand the meaning of texts). Thus, prayer and learning where believed to go hand in hand.

Monks of the Mé College (Dratsang Mé) debating, Sera-India. |  The monks of the Jé College in a prayer assembly (tsok), Sera-India. |

Tantra (sometimes referred to as Vajrayāna [Dorjé Tekpa]) is the esoteric, or secret, “vehicle” of Buddhism, an extraordinary form of Mahāyāna Buddhism that, because of its unique techniques (tap), claims to speed up the process of enlightenment, making it accessible to adepts within a single lifetime. The practice of Tantra begins with empowerment or initiation (wang) from a qualified master. In an empowerment the master will, through the process of visualization, lead the student into the palace (maṇḍala), of a specific deity. Inside the palace students are blessed by the deity/master in different ways that are said to “ripen” their minds. This ripening process is believed to be what gives students the permission to engage in tantric meditations on that specific deity.

Young monks learn to chant at the Lower Tantric College. Hunsur, India; early 1980s.

These meditations are usually enacted ritually. “Ritual” in this context refers to the chanted visualization practices wherein the words of the ritual – sung to special melodies, and accompanied by a variety of musical instruments, hand gestures, and so forth – are meant to elicit images within the mind in a scripted series of generated images that are meant to create for the meditator an enlightened or pure world to replace the world of ordinary appearances in which human beings normally live. In a typical tantric ritual, meditators visualize themselves as having the enlightened body, speech and mind of the deity that is the focus of their practice. Tantric rites can be performed for the attainment of both mundane goals (wealth, long-life, the destruction of interferences), and supramundane goals (enlightenment for the benefit of others). But it is the latter of these – the transformation, or transmutation, of the body, speech and mind into those of an enlightened being – that is considered the chief reason for engaging in the practice of Tantra.

The tantric colleges of the Geluk tradition were ritual colleges, with “ritual” being understood in the way that it has just been explained. Occasional teachings might be given about the theory or practice of Tantra, but the chief mission of the tantric colleges was to preserve Tsongkhapa’s tantric tradition through the enactment of ritual: that is, through the memorization and practice of ritual texts.

A statue of Gungru Gyeltsen Zangpo (1383-1450), from a photo in Tshe dbang rin chen, ed., Se ra theg chen gling.9

Although the historical sources are inconsistent, it would appear that it was Gungru Gyeltsen Zangpo, the third holder of the Sera throne, who was responsible for instituting the college structure at Sera. Gungruwa (1383-1450) created four colleges. He kept one of these colleges as his personal seat, and placed three of his senior students at the head of the other three colleges, as follows:

- Gungruwa: Tö or “Upper” College

- Jangchup Bumpa: Mé or “Lower” College

- Jamyang Pakpa: Gya College

- Rangjungwa (per Purchok) or Sanggyé Tsültrim (per Penchen and Desi): Dromteng or Drongteng College

Künkhyen Jangchup Bumpa (ca. fifteenth century) is to this day reckoned as the founder of the Mé College (Dratsang Mé), one of three still extant colleges of Sera. The colleges (dratsang) Gya and Dromteng eventually merged into the Töpa College (Dratsang Töpa) under another of Gungruwa’s students, Sherap Gyamtso or Shergyampa. Within a short time the Tö College itself was absorbed into a newly founded college called Jé. The Jé College (Dratsang Jé) was founded by Künkhyenpa or Müsepa Lodrö Rinchen Senggé (ca. fifteenth century). Thus it would appear that by the middle of the fifteenth century, there were only two active colleges at Sera: Jé and Mé. Both of these were philosophical colleges (tsennyi dratsang).

The four abbots of Sera, from a photo taken by F. Spencer Chapman in 1936-7. In Clare Harris and Tsering Shakya, Seeing Lhasa.10

The historical texts do not tell us when or why the colleges were consolidated. We can surmise, however, that at least two factors were involved. As is the case with most institutions, the success of a college probably had a lot to do with the charisma of its leader. The fact that the Tö College absorbed Gya and Dromteng, and that Tö was itself absorbed into Jé, may have to do with the popularity of Gungruwa (the founding lama of Tö) and of Künkhyenpa (the founding lama of Jé) as scholars and saints. But there may also have been institutional factors at work. For example, the college consolidations may have coincided with the rise of the regional house (khangtsen) as the formal subunits of colleges. As these smaller units of the colleges were institutionalized, they might have taken the place of the college as the locus of a monk’s main affiliation and as the site of his instruction. This, in turn, might have permitted the colleges to grow in size, and to absorb other colleges that were, for whatever reason, floundering. This, in any case, is one possible scenario explaining the process of college consolidation.

The third of Sera’s colleges, the Tantric College (Ngakpa Dratsang), was not founded until the eighteenth century. The Tantric College is a ritual college whose perceived mission was and is the preservation of Tsongkhapa’s tantric tradition through the enactment of a yearlong liturgical cycle of tantric rites that focus on several different deities.

Thus, from the early eighteenth century on, Sera has had three colleges: Jé, Mé, and Ngakpa. The abbotship of the defunct Töpa College (Dratsang Töpa)11 continued on as an honorary position up to 1959. Thus, Sera had four abbots, even though one of them, as the monks were fond of saying, “had no college and no monks.”

In Tibet, Sera and its colleges were shut down shortly after the uprising of 1959. All three colleges of Sera were, however, reestablished in Tibet after the liberalization of religion in the early 1980s. Their assembly halls were, for the most part, intact, and most of the images and murals in the college temples were preserved.

The Interior of the Jé College assembly hall, Sera-Tibet.

Initially, the monks who were responsible for reestablishing the monastery attempted to revive the colleges. However, because the number of monks was much smaller than it once was, in the 1990s the two philosophical colleges – Jé and Mé – decided to consolidate their educational and ritual programming. Debate sessions, for example, now take place jointly in the Jé College debate ground, and only one set of textbooks – that of the Jé College– are used. The two philosophical colleges also no longer have their own abbots, and instead share a common abbot, today mostly an honorary position. There is also no separate administration at the college level, since a monastery-wide governing board runs most of the day-to-day affairs of Sera. Instead of meeting separately in their respective college assembly halls, the monks now meet together in the Great Assembly Hall. There is one exception to this rule, however. Both colleges still observe the famous intensive, weeklong prayer assemblies that take place in the winter term. For one week the monks of Jé and smad will meet in their respective assembly halls for this “festival,” but this is the only time in the year when the monks meet in their own college assembly halls. The Tantric College, however, continues to preserve its liturgical tradition, and its monks continue to meet in their own assembly hall throughout the entire year.

The Mé College (Dratsang Mé) and Jé were also reestablished in exile in 1970, at the time of the reestablishment of Sera in the Bylakuppe settlement (Karnataka-India). In India the colleges have maintained their separate identities. They preserve their own unique educational and ritual traditions, use their own textbooks, and have their own administrative bodies. Both colleges continue to prepare monks for the geshé degree (the geshé degree is no longer granted in Tibet). Although the Tantric College was not initially reestablished in exile, it has recently been re-founded in one of the nearby refugee settlements in south India.

Click on each of the colleges to find out more about them.

Künkhyenpa, founder of the Jé College (Dratsang Jé); a statue in the Jé College assembly hall, Sera-Tibet

The Jé College is the larger of Sera’s two philosophical colleges (tsennyi dratsang). Shortly after the founding of the monastery, Künkhyenpa Lodrö Rinchen Senggé, originally a monk of Drepung Monastery, abandoned that institution with one hundred or so of his followers. Adopting Sera as their new home, Künkhyenpa and his followers established a new college that became known as jé. The word jé means “traveler,” and the college came to be known by this name because Künkhyenpa and his followers originally arrived as “travelers” from Drepung. The full, official name of the college is “Sera Jé College of Renowned Scholars (Sera Jé Khenyen Dratsang).”

Künkhyenpa was himself a great scholar (especially renowned for his mastery of madhyamaka), but he was also a visionary. When Künkhyenpa arrived at Sera he had several visions that confirmed to him that this was the place where he and his followers should settle. For example, when he made his first visit to the Assembly Hall, one of the Sixteen Arhat statues is said to have come to life and spoken to him, saying:

The travelers have arrived from their travels. This is good!

The great Künkhyenpa has arrived. This is good!

He will raise up the banner of the teachings. This is good!12

One of the Sixteen Arhats, a statue in the Jé College assembly hall, Sera-Tibet

Later, he had a vision of a series of crows, one melting into the next until the last crow melted into a wild rose bush. He took this as an indication that this was the precise site where he should build the chapel of his tutelary deity, Hayagrīva.

Under Künkhyenpa’s leadership, the Jé College quickly flourished as a center for the study of the great texts and their various “layers” of commentaries. In addition to the classical commentaries, another kind of work, the so-called “textbooks” (yikcha) became an important part of the curriculum. Although there were many textbooks by different authors in use in the college during its early days (including textbooks composed by Künkhyenpa himself), in time most of these were banned because they were seen as containing views that were at odds with those of Tsongkhapa, the founder of the order. Eventually, the textbooks written by Sera Jetsün Chöki Gyaltsén (1469-1544) became the core textbooks of the Jé College.

From the earliest days it would appear that monks lived together in informal living arrangements based on the area of the country from which they came. As the college grew, these informal units became institutionalized as the so-called “regional houses” (khangtsén). The Jé College was divided into eighteen regional houses that ranged in size from fifty to thousand monks.

Hamdong Khangtsen, the largest regional house of the Jé College, located in the northern edge of the monastery, Sera-Tibet.

Monks from different parts of Tibet would usually enter one or another of these houses depending upon the geographical region of the country from which they hailed. Here is the list of the Jé College regional houses. Click on the regional house name to see a short description of that regional house, and pictures of its headquarters in Tibet (where still extant). In that same window, next to “Regional House Affiliation,” click on the regional house name to go to a separate data-window with demographic and other information about that particular regional house.

- Hamdong

- Trehor

- Dakpo

- Ngari

- Epa

- Lhopa

- Jadrel

- Pati

- Denma

- Jetsang

- Gomdé

- Jetsa

- Lawa

- Nyelpa

- Samlo

- Gyejé

- Powo13

- Tsetang

The Jé College Assembly Hall, Sera-Tibet

The Jé College Assembly Hall is the headquarters of the college. It contains a huge meeting hall, and several ancillary chapels (lhakhang), each with its own altar and “theme.” (Click here for access to a database entry for the Jé College Assembly Hall, with pictures.) Oral tradition has it that it was one of the rear chapels of the present assembly hall that was the original assembly hall of the Jé College built by Nyeltön Peljor Lhündrup (1427-1514) in the late fifteenth century.14 The present assembly hall was built by the ruler Polhané Miwang Sönam Topgyel (1689-1747) in the early eighteenth century.

Polhané (right), the patron of the present Jé College assembly hall, and his son (left), the patron of the Hardong Khangtsén temple. From a mural in the Kongpo Khangtsen, Sera-Tibet

The most important chapel in the present temple is the abode of the Jé College tutelary deity (yidam), Hayagrīva, the “horse-headed deity,” who is the wrathful manifestation of Avalokiteśvara. This chapel is located at the north-west corner of the temple, and it is arguably the most important religious site in the entire monastery, being one of the most popular spots with pilgrims, lay worshippers, and tourists. The cult of Hayagrīva – a deity whose lineage of transmission derives from the Nyingma school – is extremely important in the Jé College, to the point where the monks of the college consider themselves, jokingly, “Yellow (that is, Geluk) on the outside, but Red (Nyingma) on the inside.” 15

The only time that the monks of the Jé College in Tibet meet together today is during the Great “Good Conduct” Prayer Meeting (Zangchö Chenmo). During this weeklong event monks spend many hours a day reciting the “Good Conduct Prayer” (Zangchö Mönlam), and lay people flock from Lhasa and surrounding areas to make offerings. Traditionally, the other major yearly event that took place at the Jé College was the daylong Dagger Blessing (Phurjel). The Jé College abbot would spend one entire day blessing monks and lay people with the famous Sera purba, a magical, ritual dagger that is said to have belonged to a famous Indian tantric saint. That event still takes place, although today it is considered a monastery-wide celebration, and not a festival exclusive to the Jé College.

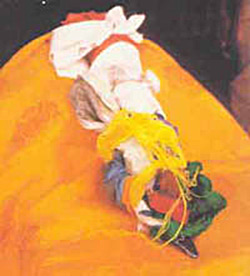

Hayagrīva, the horse-headed tutelary deity of the Jé College. Statue in the Jé College Assembly Hall, Sera-Tibet. |  The Sera purba, said to be the original ritual dagger that was in use before 1959. It is wrapped in silk. From a photo in Tshe dbang rin chen, ed., Se ra theg chen gling.16 |

The Jé College was reestablished in India in 1970, and it preserves most of the traditions of that institution as these were practiced in Tibet before 1959. This is not to say that everything is the same as it was before 1959, however. For example, the administration today is more democratic (and the abbacy less powerful) than it once was. 17 Monks are provided with three vegetarian meals a day, so that they no longer have to worry about their food (in Tibet, before 1959, many monks often went hungry). Also, in the early 1980s the Jé College in exile was innovative in founding a separate school within the college for young monks. Today, the “Sera Jé School,” as it is known, provides monks up to the age of sixteen with a well-rounded education that focuses on a variety of both traditional and modern subjects – from Tibetan language to computer science. At the age of sixteen monks enter the traditional debate-based curriculum.

The Assembly Hall of the Jé College in India |  Young monks study under the supervision of their teacher at the Sera Jé School, Sera-India |

Before 1959, the Jé College in Tibet had between five thousand and seven thousand monks. Today, in Tibet, it has about 275 monks. In India, the Jé College has about 2500 monks. Click here to gain access to more detailed demographic information and other tabular data on the Jé College.

Go on to read about the Mé College (Dratsang Mé).

Künkhyen Jangchup Bumpa, founder of the Mé College. From a photo in Se ra theg chen gling, p. 44.18

The Mé College (Dratsang Mé) is the smaller, but older, of Sera’s two philosophical colleges (tsennyi dratsang). Its official name is The Jewel-Island for Study and Contemplation (Tösam Norling). The word mé means “lower,” and the college was probably called this because it sits at a lower elevation (farther south) in Sera’s tiered landscape. Shortly after the founding of the monastery, the third holder of the Sera throne divided the institution up into various sections or colleges, appointing his senior students as preceptors of these different sections. Künkhyen Jangchup Bumpa (fifteenth century) was appointed preceptor (loppön) of the Mé section, and today he is reckoned as its founder.

In time, the Mé College evolved a fixed educational curriculum that focused on the study of the great Indian Buddhist classics. As was the case with the Jé College (Dratsang Jé), there appears to have been a good deal of diversity in the types of textbooks (yikcha) used in the early days of the Mé College. Geshé Yeshé Wangchuk, a contemporary historian, for example, tells us that the textbooks of Gungru Gyeltsen Zangpo, the third Sera throne-holder, were popular for almost a century at Mé. Eventually, however, these early textbooks were banned in favor of the textbooks of Khedrup Tenpa Dargyé. Although the chief mission of the Mé College was to instruct monks in the exoteric, philosophical/textual tradition, less than 25 percent of all monks in the college were textualists (pechawa). The remaining monks were mostly workers.

The assembly hall of the Mé College, Sera-Tibet.

The center of the college, where its administration was housed and where its abbot lived, was the assembly hall (dukhang). The present Mé assembly hall in Tibet, built in 1761 by the Seventh Demo Rinpoché (Demo Rinpoché Dünpa), Demo Delek Gyatso, contains a huge meeting hall and several ancillary chapels (lhakhang), each with its own altar and “theme.” Click here to gain access to a database entry on the Mé College assembly hall, with photos.

The most important of the smaller chapels inside the Mé College is the Taok Protector Chapel (Taok Gönkhang) located in the northwest corner of the temple. View a video of the Taok Chapel in which the Ven. Tsültrim, the caretaker, gives a guided tour of this chapel (to play this video you must have the free QuickTime player installed on your computer). The tour is in Tibetan.

The Tsador Regional House was one of the mid-size regional houses of the Mé College, Sera-Tibet

Philosophical colleges were divided into smaller units called regional houses (khangtsen). The Mé College was divided into sixteen regional houses, which ranged in size from fifty to several hundred monks. Monks from different parts of Tibet would usually enter one or another of these houses depending upon the geographical region of the country from which they hailed. Here are the regional houses of the Mé College. Click on the regional house name to see a brief narrative description about that particular regional house, and to access photos of its headquarters (where still extant). In that window, beside “Regional House Affiliation,” click on the regional house name to go to a data-window with demographic and other information about that particular regional house.

- Zhungpa

- Pombor

- Gyelrong

- Metsa

- Kongpo

- Yerpa

- Metsang

- Tsador

- Tawen

- Rongpo

- Gungru

- Minyak

- Tewo

- Ara

- Marnyung

- Powo

In Tibet today the Mé College has lost many of the traits that made it a unique institution. Since the consolidation of the Jé and Mé Colleges in the 1990s, the monks of both colleges meet together for all educational activities. So, for example, debate sessions now take place jointly: only in the Jé College debate ground. Monks also only use one set of textbooks – that of the Jé College.19 The Jé and Mé monks also meet together for all of their ritual activities. There is one exception to this rule, however. Both colleges still observe the famous intensive, weeklong prayer assemblies that take place in the winter term. For one week the monks of Jé and Mé will meet in their respective assembly halls. The event at the Mé College is called the Great “Maitreya” Prayer Meeting (Jammön Chenmo). During this weeklong event the monks of the Mé College spend many hours each day reciting a prayer to the future Buddha, Maitreya (Jampa), and laypeople flock from Lhasa and the surrounding areas to make offerings.

It was dedicated by His Holiness the Dalai Lama in the summer of 2003. The Mé College was also reestablished in exile in 1970, at the time of the refounding of Sera in the Bylakuppe settlement (Karnataka, India). Unlike the Mé College in Tibet, in India the college continues to retain its individual institutional identity, preserving its own unique educational/ritual practices and its own administration.

The newly built Mé College Assembly hall (dukhang) in Sera-India. |  Young monks on their way to classes at the Sera Mé College, Sera-India. |

In the mid-1980s, following the example of the Jé College, the Mé College in India founded a separate school within the college for young monks. Today, the “Sera Mé School,” as it is known, provides monks up to the age of sixteen with a well-rounded education in a variety of both traditional and modern subjects – from Buddhist philosophy to world geography. At the age of sixteen, monks then enter the traditional debate-based curriculum. Before 1959, the Mé College in Tibet had between three thousand and five thousand monks. Today, in Tibet, it has about 125 monks. In India, the Mé College has about 1500 monks. Click here to gain access to more detailed demographic information and other tabular data related to the Mé College. Click here to learn about the Tantric College (Ngakpa Dratsang).

The Tantric College (Ngakpa Dratsang) of Sera is an institution devoted exclusively to the practice of tantric ritual/meditation. There is some evidence that monks studied philosophy in some of the other tantric colleges of the Geluk tradition, but this appears never to have been the case at Sera. Instead, the Sera Tantric College (Sera Ngakpa Dratsang) seems to have been conceived of as a strictly ritual college from the start.

The Mongolian ruler of Tibet Lhazang Khang (d. 1717), on whose behalf the Tantric College was founded |  The façade of the Sera Tantric College. Sera-Tibet |

The Tantric College is the youngest of Sera’s three colleges. It was founded in the early eighteenth century as the personal ritual college of the then ruler of Tibet, Lhazang Khang. The present assembly hall of the Tantric College was the original assembly hall for all of Sera.20 By the early eighteenth century, however (and probably much earlier) that temple was already too small to house all of the monks of Sera when they met jointly. When Lhazang Khang came to power, he promised to build a new assembly hall (the present Great Assembly Hall), if the old assembly hall was converted into a private Tantric Ritual College (Kurim Dratsang): an institution that would devote itself exclusively to the performance of rituals on his behalf. The monks agreed, and the old assembly hall was converted into a ritual college. Later, this became the Tantric College, but the fact that the college still performs rituals related to, for example, the Nine Long-life Gods (Tsepak Lhagu), may be a vestige from the time that the college performed rituals on behalf of Lhazang Khang.

The apartment house of the Tantric College (Sera-Tibet), located just behind (north) of the Tantric College assembly hall. Before 1959 this probably belonged to the Metsang Regional House.

Before 1959 the Tantric College had no regional houses or apartment buildings. Its monks lived in the regional houses of the philosophical colleges (principally in the houses of Mé College [Dratsang Mé]), where they borrowed or rented rooms. Today, the Tantric College owns one large apartment house, formerly owned by the Metsang Regional House (Metsang Khangtsen), which in 2003 had been recently renovated. It is unclear why the Tantric College never built a dormitory for its monks before 1959. Perhaps there was no space for such a building already by the eighteenth century, when the Tantric College was founded. More likely, there was perhaps no need for such a regional house during that time, since the monks that populated the new Tantric College may simply have been drawn from the existing monastic populations of the Jé and Mé Colleges (where they presumably already had rooms, and already belonged to regional houses). Politics may have also played a part in this, however. Since the regional houses had considerable political power within the monastery, it is not inconceivable that the two philosophical colleges might have blocked the creation of Tantric College regional houses, since agreeing to the creation of such units would have undoubtedly committed them to sharing power.

In contrast to Sera’s two other colleges – Jé and Mé – the Tantric College is an institution almost entirely concerned with the practice of ritual. Before 1959, the Tantric College had a fixed, yearly liturgical cycle focusing on five major sets of deities. Click on the deity’s name to see an image of the deity on www.himalayanart.org

- Guhyasamāja (cycle celebrated in the twelfth Tibetan month)

- Cakrasaṃvara (tenth Tibetan month)

- Yamāntaka (sixth Tibetan month)

- Sarvavid (Vairocana, fourth Tibetan month)

- The Nine Long-Life Gods (Tsepak Lhagu, second Tibetan month)

In a typical ritual cycle (chötok) – which may run several weeks – the monks gather in the Tantric College assembly hall, they perform the self-initiation ritual (danjuk) and construct from colored sands the maṇḍala of the deity of that particular cycle. They then spend the bulk of the ritual cycle performing the self-generation ritual (dakyé) of the deity four times a day until they have accumulated the requisite number of mantra repetitions. At the conclusion of the cycle, they perform a burnt-offering ritual (jinsek) to purify any faults or omissions committed during the retreat cycle.

Monks of the Tantric College break for lunch during one of their ritual cycles. Sera-Tibet. |  Monks of the Tantric College (Sera-Tibet) perform the burnt-offering ritual in the assembly-hall courtyard at the end of the Yamāntaka ritual cycle in July of 2002. |

Before 1959 the Tantric College had about a thousand monks, and the vast majority of these monks came from Central Tibet (mostly from Lhasa).21 Like all of Sera’s institutions, the Tantric College in Tibet effectively ceased to exist from 1959 until the monastery was allowed to reopen in the early 1980s. Today, it has a monastic population of about one hundred monks. Click here to gain access to pictures of the Tantric College, including many images of the Yamāntaka burnt-offering ritual. In that window click the word sngags pa, next to “College Affiliation,” to gain access to a data window that contains demographic and other information about the Tantric College.

The Jé and Mé Colleges share an abbot and have lost many of their individual traditions since their consolidation in the 1990s. The Tantric College, by contrast, retains the tradition of having its own abbot, and it continues to perform all of its ritual cycles in its own assembly hall. Like all of Sera’s colleges, however, it is under the general administrative aegis of the Sera-wide “democratic governing board.”

In India, the Tantric College was not refounded until the late 1990s. It is not part of the Sera complex in the Bylakuppe settlement, but instead exists as a separate institution in another nearby settlement.

Note: The glossary is organized into sections according to the main language of each entry. The first section contains Tibetan words organized in Tibetan alphabetical order. To jump to the entries that begin with a particular Tibetan root letter, click on that letter below. Columns of information for all entries are listed in this order: THL Extended Wylie transliteration of the term, THL Phonetic rendering of the term, the English translation, the Sanskrit equivalent, associated dates, and the type of term. To view the glossary sorted by any one of these rubrics, click on the corresponding label (such as “Phonetics”) at the top of its column.

| Ka | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kun mkhyen pa | Künkhyenpa | Person | |||

| kun mkhyen byang chub ’bum pa | Künkhyen Jangchup Bumpa | fifteenth century | Person | ||

| kun mkhyen blo gros rin chen seng ge | Künkhyen Lodrö Rinchen Senggé | fifteenth century | Person | ||

| kong po | Kongpo | Regional house | |||

| kong po khang tshan | Kongpo Khangtsen | Regional house | |||

| sku rim | kurim | ritual | Term | ||

| sku rim grwa tshang | Kurim Dratsang | Tantric Ritual College | Monastery | ||

| Kha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| khang tshan | khangtsen | regional house | Term | ||

| khungs | khung | affiliation | Term | ||

| khri pa | tripa | throne-holder | Term | ||

| mkhan po | khenpo | abbot | Term | ||

| mkhas grub dge legs dpal bzang | Khedrup Gelek Pelzang | 1385-1438 | Person | ||

| mkhas grub bstan dar | Khedrup Tendar | 1493-1568 | Person | ||

| mkhas grub bstan pa dar rgyas | Khedrup Tenpa Dargyé | 1493-1568 | Person | ||

| Ga | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| gung ru | Gungru | Regional house | |||

| gung ru rgyal mtshan bzang po | Gungru Gyeltsen Zangpo | 1383-1450 | Person | ||

| gung ru ba | Gungruwa | 1383-1450 | Person | ||

| grwa tshang | dratsang | monastic college | Term | ||

| grwa tshang stod | Dratsang Tö | Tö College | Monastery | ||

| grwa tshang stod pa | Dratsang Töpa | Töpa College | Monastery | ||

| grwa tshang byas dang smad | Dratsang Jé dang Mé | Jé and Mé Colleges | Monastery | ||

| grwa tshang byes | Dratsang Jé | Jé College | Monastery | ||

| grwa tshang blo gsal gling | Dratsang Loselling | Loseling College | Monastery | ||

| grwa tshang smad | Dratsang Mé | Mé College | Monastery | ||

| dga’ ldan | Ganden | Monastery | |||

| dge lugs | Geluk | Organization | |||

| dge lugs pa | Gelukpa | Organization | |||

| dge lugs pa’i mtshan nyid grwa tshang | Gelukpé tsennyi dratsang | Gelukpa philosophical college | Term | ||

| dge bshes | geshé | Term | |||

| dge bshes ye shes dbang phyug | Geshé Yeshé Wangchuk | Person | |||

| rgya | Gya | Monastery | |||

| rgyal ba | Gyelwa | Monastery | |||

| rgyal rong | Gyelrong | Regional house | |||

| rgyas byes | Gyejé | Regional house | |||

| rgyud | gyü | tantra | Term | ||

| sgo mang | Gomang | Monastery | |||

| sgom sde | Gomdé | Regional house | |||

| Nga | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| nges ’byung | ngenjung | renunciation | Term | ||

| mnga’ ris | Ngari | Regional house | |||

| sngags pa | ngakpa | tantric | Term | ||

| sngags pa grwa tshang | Ngakpa Dratsang | Tantric College | Monastery | ||

| Cha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| chos thog | chötok | ritual cycle | Term | ||

| ’chad nyan pa | chenyenpa | instructor | Term | ||

| Ja | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| ’jang dgun chos | Jang Günchö | Special Winter Interterm | Term | ||

| ’jam dbyangs chos rje | Jamyang Chöjé | 1379-1449 | Person | ||

| ’jam dbyangs ’phags pa | Jamyang Pakpa | Person | |||

| Nya | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| gnyal ston dpal ’byor lhun grub | Nyeltön Penjor Lhündrup | 1427-1514 | Person | ||

| gnyal pa | Nyelpa | Regional house | |||

| rnying ma | Nyingma | Organization | |||

| Ta | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| tā dben | Tawen | Regional house | |||

| tre hor | Trehor | Regional house | |||

| stod | tö | upper | Term | ||

| stod pa | Töpa | Monastery | |||

| Tha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| tha ’og mgon khang | Taok Gönkhang | Taok Protector Chapel | Building | ||

| thabs | tap | technique | Term | ||

| the bo | Tewo | Regional house | |||

| thos bsam gling | Tösamling | Monastery | |||

| thos bsam nor gling | Tösam Norling | The Jewel-Island for Study and Contemplation | Monastery | ||

| Da | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| de mo bde legs rgya mtsho | Demo Delek Gyatso | d. 1777 | Person | ||

| de mo rin po che mdun pa | Demo Rinpoché Dünpa | Seventh Demo Rinpoché | d. 1777 | Person | |

| dwags po | Dakpo | Regional house | |||

| gdan sa | densa | large monastic academy | Term | ||

| bdag bskyed | dakyé | self-generation ritual | Ritual | ||

| bdag ’jug | danjuk | self-initiation ritual | Ritual | ||

| bde yangs | Deyang | Monastery | |||

| ’du khang | dukhang | assembly hall | Term | ||

| ’dul ba | Dülwa | Monastic Discipline | Doxographical Category | ||

| ’dul ba pa | Dülwapa | Vinaya College | Organization | ||

| ’den ma | Denma | Regional house | |||

| rdo rje theg pa | Dorjé Tekpa | Vajrayāna | Doxographical Category | ||

| sde srid sangs rgyas rgya mtsho | Desi Sanggyé Gyatso | Person | |||

| bsdus grwa | Düdra | Collected Topics | Doxographical Category | ||

| Pa | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| paṇ chen | Penchen | Person | |||

| dpe klog rgyab pa | pelok gyappa | reading | Term | ||

| dpe khrid | petri | oral commentary on the texts | Term | ||

| dpe cha ba | pechawa | textualist | Term | ||

| spa ti | Pati | Regional house | |||

| spo bo | Powo | Regional house | |||

| spo bo khang tshan | Powo Khangtsen | Regional house | |||

| Pha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| phar phyin | Parchin | Perfection of Wisdom | Doxographical Category | ||

| phur lcog | Purchok | Person | |||

| phur mjal | Purjel | Dagger Blessing | Ritual | ||

| phur ba | purba | ritual dagger | Term | ||

| pho lha gnas mi dbang bsod nams stobs rgyal | Polhané Miwang Sönam Topgyel | 1689-1747 | Person | ||

| Ba | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| bya bral | Jadrel | Regional house | |||

| byang chub kyi sems | jangchupkyi sem | thought of enlightenment | Term | ||

| byang chub ’bum pa | Jangchup Bumpa | Person | |||

| byams chen chos rje | Jamchen Chöjé | 1354-1435 | Person | ||

| byams pa | Jampa | future Buddha, Maitreya | Maitreya | Buddhist deity | |

| byams smon chen mo | Jammön Chenmo | Great Maitreya Prayer Meeting | Festival | ||

| byes | Jé | Monastery | |||

| byes grwa tshang | Jé Dratsang | Jé College | Monastery | ||

| byes ’du khang | Jé Dukhang | Jé College Assembly Hall | Building | ||

| byes tsang | Jetsang | Regional house | |||

| byes tsha | Jetsa | Regional house | |||

| bla ma | lama | master | Term | ||

| blo ’dzin | löndzin | memorization | Term | ||

| blo gsal gling | Loselling | Monastery | |||

| dbang | wang | empowerment or initiation | Term | ||

| dbu ma | Uma | The Theory of Emptiness | Madhyamaka | Doxographical Category | |

| ’bras spungs | Drepung | Monastery | |||

| ’brong steng | Drongteng | Monastery | |||

| ’brom steng | Dromteng | Monastery | |||

| sba ti | Bati | Regional house | |||

| sbyin sreg | jinsek | burnt-offering ritual | Ritual | ||

| Ma | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| mar nyung | Marnyung | Regional house | |||

| mi nyag | Minyak | Regional house | |||

| mi rigs dpe skrun khang | Mirik Petrünkhang | Publisher tibetan | |||

| mus srad pa blo gros rin chen seng ge | Müsepa Lodrö Rinchen Senggé | fifteenth century | Person | ||

| smad | Mé | Monastery | |||

| smad gtsang | Metsang | Regional house | |||

| smad tsha | Metsa | Regional house | |||

| smad tshang khang tshan | Metsang Khangtsen | Metsang Regional House | Regional house | ||

| Tsa | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| tsang pa khang tshan | Tsangpa Khangtsen | Regional house | |||

| tsong kha pa | Tsongkhapa | 1357-1419 | Person | ||

| rtsed thang | Tsetang | Regional house | |||

| rtsod pa | tsöpa | debate | Term | ||

| Tsha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| tsha rdor | Tsador | Regional house | |||

| tshad ma | Tsema | Logic/epistemology | pramāṇa | Doxographical Category | |

| tshul khrims | Tsültrim | Person | |||

| tshe dpag lha dgu | Tsepak Lhagu | Nine Long-life Gods | Buddhist deity | ||

| tshe dbang rin chen | Tsewang Rinchen | Person | |||

| tshogs | tsok | prayer assembly | Term | ||

| mtshan nyid grwa tshang | tsennyi dratsang | philosophical college | Term | ||

| Dza | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| mdzod | Dzö | Metaphysics/Cosmology | Doxographical Category | ||

| Zha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| gzhung pa | Zhungpa | Regional house | |||

| Za | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| bzang spyod chen mo | Zangchö Chenmo | Great “Good Conduct” Prayer Meeting | Festival | ||

| bzang spyod smon lam | Zangchö Mönlam | “Good Conduct” Prayer | Festival | ||

| Ya | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| yang dag pa’i lta ba | yangdakpé tawa | right view | Term | ||

| yi dam | yidam | tutelary deity | Term | ||

| yig cha | yikcha | textbook | Term | ||

| yer pa | Yerpa | Regional house | |||

| Ra | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| rang byung ba | Rangjungwa | Person | |||

| rong po | Rongpo | Regional house | |||

| La | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| lwa ba | Lawa | Regional house | |||

| lam rim | lamrim | stages of the path | Term | ||

| Sha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| shag skor | Shakkor | Organization | |||

| sher rgyam pa | Shergyampa | Person | |||

| shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa | Sherapkyi Paröltu Chinpa | Perfection of Wisdom | Prajñāpāramitā | Doxographical Category | |

| shes rab rgya mtsho | Sherap Gyamtso | Person | |||

| Sa | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| sa skya | Sakya | Organization | |||

| sangs rgyas tshul khrims | Sanggyé Tsültrim | Person | |||

| se ra | Sera | Monastery | |||

| se ra sngags pa grwa tshang | Sera Ngakpa Dratsang | Sera Tantric College | Monastery | ||

| se ra rje btsun chos kyi rgyal mtshan | Sera Jetsün Chökyi Gyeltsen | 1469-1544 | Person | ||

| se ra theg chen gling | Sera Tekchen Ling | Monastery | |||

| se ra byes | Sera Jé | Monastery | |||

| se ra byes mkhas snyan grwa tshang | Sera Jé Khenyen Dratsang | Sera Jé College of Renowned Scholars | Monastery | ||

| slob dpon | loppön | preceptor | Term | ||

| gsang phu | Sangpu | Monastery | |||

| gsang phu sne’u thog | Sangpu Neutok | Monastery | |||

| gsang ba rdo rje | Sangwa Dorjé | Guhyavajra | Buddhist deity | ||

| bsam lo | Samlo | Regional house | |||

| Ha | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| har gdong | Hamdong | Regional house | |||

| har gdong khang tshan | Hamdong Khangtsen | Regional house | |||

| lha khang | lhakhang | chapel | Room | ||

| lha bzang khāng | Lhazang Khang | d. 1717 | Person | ||

| lha sa | Lhasa | Place | |||

| lho pa | Lhopa | Regional house | |||

| A | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| a ra | Ara | Regional house | |||

| e pa | Epa | Regional house | |||

| Sanskrit | |||||

| Extended Wylie | Phonetics | English | Sanskrit | Date | Type |

| arhat | Term | ||||

| Avalokiteśvara | Buddhist deity | ||||

| Buddha | Buddhist deity | ||||

| Cakrasaṃvara | Buddhist deity | ||||

| Lord of Reasoning | Dharmakīrti | Person | |||

| Guhyasamāja | Buddhist deity | ||||

| Hayagrīva | Buddhist deity | ||||

| philosophy of emptiness | Madhyamaka | Doxographical Category | |||

| Mahāyāna | Doxographical Category | ||||

| maṇḍala | Term | ||||

| Nālanda | Monastery | ||||

| Sarvavid | Buddhist deity | ||||

| Vairocana | Buddhist deity | ||||

| Vikramaśīla | Monastery | ||||

| Yamāntaka | Buddhist deity | ||||